Before diving into understanding how EVM works and seeing it working via code examples, let’s see where EVM fits in the Ethereum and what are its components.

The below diagram shows where EVM fits into Ethereum.

The next one, shows the EVM architecture as a simple stack-based arch.

Finally we can see here the EVM execution model.

Smart contracts are just computer programs, and we can say that Ethereum contracts are smart contracts that run on the Ethereum Virtual Machine. The EVM is the sandboxed runtime and a completely isolated environment for smart contracts in Ethereum. This means that every smart contract running inside the EVM has no access to the network, file system, or other processes running on the computer hosting the VM.

As we already know, there are two kinds of accounts: contracts and external accounts. Every account is identified by an address, and all accounts share the same address space. The EVM handles addresses of 160-bit length.

Every account consists of a balance, a nonce, bytecode, and stored data (storage). However, there are some differences between these two kinds of accounts:

-

Code and storage of external owned accounts are empty while contract ones store their bytecode and the merkle root hash of the entire state tree (WHY the root?).

-

EOA are controlled by a Sk (Secret/Private key) while contracts are controlled by it's code, executed by the EVM.

The EVM manages different kinds of data depending on their context, and it does that in different ways. We can distinguish at least four main types of data: stack, calldata, memory, and storage, besides the contract code. Let’s analyze each of these:

The EVM is a stack machine, meaning that it doesn’t operate on registers but on a virtual stack. The stack has a maximum size of 1024. Stack items have a size of 256 bits; in fact, the EVM is a 256-bit word machine (this facilitates Keccak256 hash scheme and elliptic-curve computations but makes iterate through an array with a uint8 or add tho uint16 values much more hard).

POPremoves item from the stack.PUSHnplaces the following n bytes item in the stack, with n from 1 to 32.DUPnduplicates the nth stack item, with n from 1 to 32.SWAPnexchanges the 1st and nth stack item, with n from 1 to 32.

The calldata is a read-only byte-addressable space where the data parameter of a transaction or call is held. Unlike the stack, to use this data you have to specify an exact byte offset and number of bytes you want to read. This is how an external function in Solidity manages it's data arguments.

The opcodes provided by the EVM to operate with the calldata include:

CALLDATASIZEtells the size of the transaction data.CALLDATALOADloads 32 bytes of the transaction data onto the stack.CALLDATACOPYcopies a number of bytes of the transaction data to memory.

Solidity also provides an inline assembly version of these opcodes. These are calldatasize, calldataload and calldatacopy respectively. The last one expects three arguments (t, f, s): it will copy s bytes of calldata at position f into memory at position t. In addition, Solidity lets you access to the calldata through msg.data.

Let’s analyze another example using calldata:

contract Calldata {

function add(uint256 _a, uint256 _b) public view

returns (uint256 result)

{

assembly {

let a := mload(0x40)

let b := add(a, 32)

calldatacopy(a, 4, 32)

calldatacopy(b, add(4, 32), 32)

result := add(mload(a), mload(b))

}

}

}Note that we can writte assembly code on our Solidity code as wee see on the example avobe by typing assembly {..incomprensible instructions...}.

What we are doing here is the following:

- We are storing that memory pointer in the variable

aand storing inbthe following position which is 32-bytes right aftera. - Then we use

calldatacopyto store the first parameter ina. You may have noticed we are copying it from the 4th position of the calldata instead of its beginning. This is because the first 4 bytes of the calldata hold the signature of the function being called, in this casebytes4(keccak256("add(uint256,uint256)")).

This bytes4(keccak256("add(uint256,uint256)")) is what EVM uses to identify which function has to be executed on the call.

Then, we store the second parameter in b copying the following 32 bytes of the calldata. Finally, we just need to calculate the addition of both values loading them from memory.

Memory is a volatile read-write byte-addressable space. It is mainly used to store data during execution, mostly for passing arguments to internal functions. Given this is volatile area, every message call starts with a cleared memory. All locations are initially defined as zero. As calldata, memory can be addressed at byte level, but can only read 32-byte words at a time. It's curious that is able to write 256-bit and 8-bit memmory positions, but just able to read 256-bit words.

Memory is said to “expand” when we write to a word in it that was not previously used. Additionally to the cost of the write itself, there is a cost to this expansion, which increases linearly for the first 724 bytes and quadratically after that.

The EVM provides three opcodes to interact with the memory area:

`MLOAD` loads a 32-byte word from memory into the stack.

`MSTORE` saves a 32-byte word to memory.

`MSTORE8` saves a byte to memory.

Solidity also provides an inline assembly version of these opcodes. There is another key thing we need to know about memory.** Solidity always stores a free memory pointer at position 0x40**, i.e. a reference to the first unused word in memory. That’s why we load this word to operate with inline assembly on the example avobe. Since the initial 64 bytes of memory are reserved for the EVM, this is how we can ensure that we are not overwriting memory that is used internally by Solidity.

For instance, in the delegatecall example presented above, we were loading this pointer to store the given calldata to forward it. This is because the inline-assembly opcode delegatecall needs to fetch its payload from memory.

Additionally, if you pay attention to the bytecode output by the Solidity compiler, you will notice that all of them start with 0x6060604052…, which means:

PUSH1 : EVM opcode is 0x60

0x60 : The free memory pointer

PUSH1 : EVM opcode is 0x60

0x40 : Memory position for the free memory pointer

MSTORE : EVM opcode is 0x52

We must be very careful when operating with memory at assembly level. Otherwise, we could overwrite a reserved space.

Storage is a persistent read-write word-addressable space. This is where each contract stores its persistent information. Unlike memory, storage is a persistent area and can only be addressed by words. It is a key-value mapping of 2²⁵⁶ slots of 32 bytes each. A contract can neither read or write to any storage apart from its own. All locations are initially defined as zero.

The amount of gas required to save data into storage is one of the highest among alll operations of the EVM. This cost is not always the same. Modifying a storage slot from a zero value to a non-zero one costs 20,000. While storing the same non-zero value or setting a non-zero value to zero costs 5,000. However, in the last scenario when a non-zero value is set to zero, a refund of 15,000 will be given.

The EVM provides two opcodes to operate the storage:

`SLOAD` loads a word from storage into the stack.

`SSTORE` saves a word to storage.

These opcodes are also supported by the inline assembly of Solidity.

Solidity will automatically map every defined state variable of your contract to a slot in storage. The strategy is fairly simple — statically sized variables (everything except mappings and dynamic arrays) are laid out contiguously in storage starting from position 0.

For dynamic arrays, this slot (p) stores the length of the array and its data will be located at the slot number that results from hashing p(keccak256(p)). For mappings, this slot is unused and the value corresponding to a key k will be located at keccak256(k,p). Bear in mind that the parameters of keccak256 (k and p) are always padded to 32 bytes.

The first thing that happens when a new contract is deployed to the Ethereum blockchain is that its account is created (identified).

As the next step, the data sent in with the transaction is executed as bytecode. This will initialize the state variables in storage, and determine the body of the contract being created. This process is executed only once during the lifecycle of a contract. The initialization code is not what is stored in the contract; it actually produces as its return value the bytecode to be stored. Bear in mind that after a contract account has been created, there is no way to change its code.

Given the fact that the initialization process returns the code of the contract’s body to be stored, it makes sense that this code isn’t reachable from the constructor logic.

contract Impossible {

function Impossible() public {

this.test();

}

function test() public pure returns(uint256) {

return 2;

}

}If you try to compile this contract, you will get a warning saying you’re referencing this within the constructor function, but it will compile. However, if you try to deploy a new instance, it will revert. This is because it makes no sense to attempt to run code that is not stored yet. (The EVM will check before calling an external function that the contract's address has bytecode in it. And otherwise, revert). On the other hand, we were able to access the address of the contract: the account exists, but it doesn’t have any code yet.

However, a code execution can produce other events, such as altering the storage, creating further accounts, or making further message calls.

Additionally, contracts can be created using the CREATE opcode, which is what the Solidity new construct compiles down to.

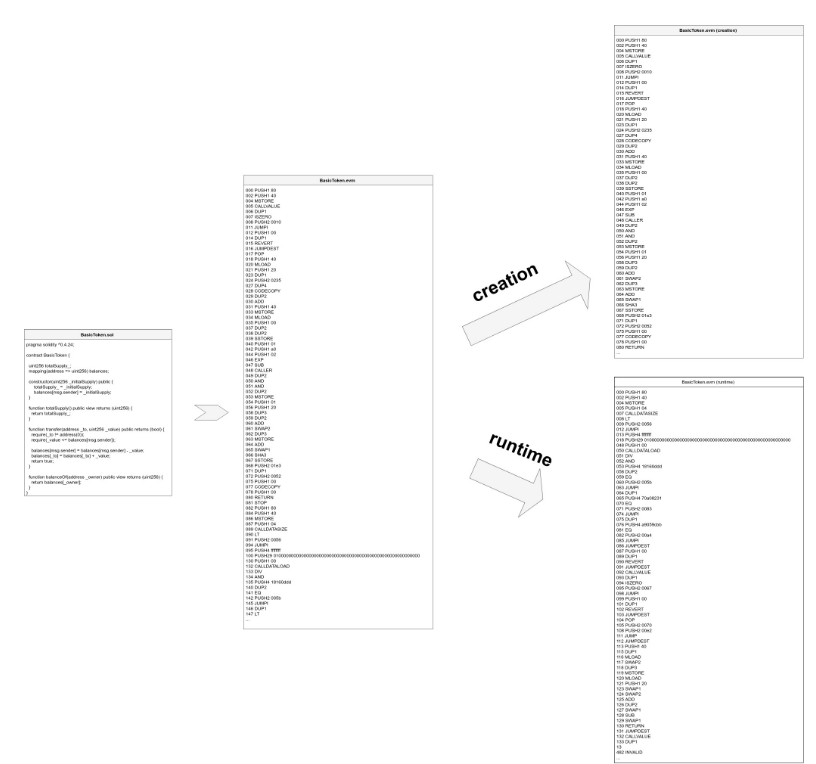

So this will be the example of a function call. In our case, Constructor function:

When we compile a contract from our Solidity code, we obtain as a result a bunch of bytes (the bytecode of that contract) which looks like:

608060405234801561001057600080fd5b5060405160208061021783398101604090815290516000818155338152600160205291909120556101d1806100466000396000f3006080604052600436106100565763ffffffff7c010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000060003504166318160ddd811461005b57806370a0823114610082578063a9059cbb146100b0575b600080fd5b34801561006757600080fd5b506100706100f5565b60408051918252519081900360200190f35b34801561008e57600080fd5b5061007073ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff600435166100fb565b3480156100bc57600080fd5b506100e173ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff60043516602435610123565b604080519115158252519081900360200190f35b60005490565b73ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff1660009081526001602052604090205490565b600073ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff8316151561014757600080fd5b3360009081526001602052604090205482111561016357600080fd5b503360009081526001602081905260408083208054859003905573ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff85168352909120805483019055929150505600a165627a7a72305820a5d999f4459642872a29be93a490575d345e40fc91a7cccb2cf29c88bcdaf3be0029

Which is the Bytecode of the contract:

pragma solidity ^0.4.24;

contract BasicToken {

uint256 totalSupply_;

mapping(address => uint256) balances;

constructor(uint256 _initialSupply) public {

totalSupply_ = _initialSupply;

balances[msg.sender] = _initialSupply;

}

function totalSupply() public view returns (uint256) {

return totalSupply_;

}

function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) public returns (bool) {

require(_to != address(0));

require(_value <= balances[msg.sender]);

balances[msg.sender] = balances[msg.sender] - _value;

balances[_to] = balances[_to] + _value;

return true;

}

function balanceOf(address _owner) public view returns (uint256) {

return balances[_owner];

}

}When we send this bytecode to deploy a contract. This transaction is sent to the 0x0 address, and as a result, a new contract instance is created with it's own address and code. It'll be reviewed in depth later.

With tools like Remix, we can make the bytecode more "Readable" by looking at the Debbugger tab.

The previous bytecode will be associated to this Instructions:

000 PUSH1 80

002 PUSH1 40

004 MSTORE

005 CALLVALUE

006 DUP1

007 ISZERO

008 PUSH2 0010

011 JUMPI

012 PUSH1 00

014 DUP1

015 REVERT

016 JUMPDEST

017 POP

018 PUSH1 40

020 MLOAD

021 PUSH1 20

023 DUP1

024 PUSH2 0217

027 DUP4

028 CODECOPY

029 DUP2

030 ADD

031 PUSH1 40

033 SWAP1

034 DUP2

035 MSTORE

036 SWAP1

037 MLOAD

038 PUSH1 00

040 DUP2

041 DUP2

042 SSTORE

043 CALLER

044 DUP2

045 MSTORE

046 PUSH1 01

048 PUSH1 20

050 MSTORE

051 SWAP2

… (abbreviated)This is the disassembled bytecode of the contract. Disassembly sounds rather intimidating, but it’s quite simple, really. If you scan the raw bytecode by bytes (two characters at a time), the EVM identifies specific opcodes that it associates to particular actions. For example:

0x60 => PUSH

0x01 => ADD

0x02 => MUL

0x00 => STOP

...Before we get started on our ambitious endeavour of completely deconstructing the bytecode, you’re going to need a basic tool set for understanding individual opcodes such as PUSH, ADD, SWAP, DUP, etc. An opcode, in the end, can only push or consume items from the EVM’s stack, memory, or storage belonging to the contract. That’s it.

Opcodes can be find here: https://github.com/ethereum/pyethereum/blob/develop/ethereum/opcodes.py

Each line in the disassembled code above is an instruction for the EVM to execute as we mentioned before. Each instruction contains an opcode. For example, let’s take one of those instructions, instruction 88, which pushes the number 4 to the stack. This particular disassembler interprets instructions as follows:

88 PUSH1 0x04

| | |

| | Hex value for push.

| Opcode.

Instruction number.

We’ll identify split points in the disassembled code and reduce it bit by bit, until we end up with small, digestible chunks, which we’ll walk through step by step in Remix’s debugger. In the following diagram, we can see the first split we can make on the disassembled code, which we’ll analyze:

When the EVM executes code, it does so top down with no exceptions — i.e., there are no other entry points to the code. It always starts from the top. It can jump around, yes, and that’s exactly what JUMP and JUMPI do.

JUMPtakes the topmost value from the stack and moves execution to that location. The target location must contain aJUMPDESTopcode, though, otherwise execution will fail.- That is the sole purpose of

JUMPDEST: to mark a location as a valid jump target. JUMPIis exactly the same,but there must not be a “0” in the second position of the stack, otherwise there will be no jump. So this is a conditional jump.STOPcompletely halts execution of the contract.RETURNhalts execution too, but returns data from a portion of the EVM’s memory, which is handy.

And this are our instructions:

000 PUSH1 80

002 PUSH1 40

004 MSTORE

005 CALLVALUE

006 DUP1

007 ISZERO

008 PUSH2 0010

011 JUMPI

012 PUSH1 00

014 DUP1

015 REVERT

016 JUMPDEST

017 POP

018 PUSH1 40

020 MLOAD

021 PUSH1 20

023 DUP1

024 PUSH2 0217

027 DUP4

028 CODECOPY

029 DUP2

030 ADD

031 PUSH1 40

033 SWAP1

034 DUP2

035 MSTORE

036 SWAP1

037 MLOAD

038 PUSH1 00

040 DUP2

041 DUP2

042 SSTORE

043 CALLER

044 DUP2

045 MSTORE

046 PUSH1 01

048 PUSH1 20

050 MSTORE

051 SWAP2

052 SWAP1

053 SWAP2

054 SHA3

055 SSTORE

056 PUSH2 01d1

059 DUP1

060 PUSH2 0046

063 PUSH1 00

065 CODECOPY

066 PUSH1 00

068 RETURN

069 STOP

070 PUSH1 80

072 PUSH1 40

074 MSTORE

075 PUSH1 04

077 CALLDATASIZE

078 LT

079 PUSH2 0056

082 JUMPI

083 PUSH4 ffffffff

088 PUSH29 0100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

118 PUSH1 00

120 CALLDATALOAD

121 DIV

122 AND

123 PUSH4 18160ddd

128 DUP2

129 EQ

130 PUSH2 005b

133 JUMPI

134 DUP1

135 PUSH4 70a08231

140 EQ

141 PUSH2 0082

144 JUMPI

145 DUP1

146 PUSH4 a9059cbb

151 EQ

152 PUSH2 00b0

155 JUMPI

156 JUMPDEST

157 PUSH1 00

159 DUP1

160 REVERT

161 JUMPDEST

162 CALLVALUE

163 DUP1

164 ISZERO

165 PUSH2 0067

168 JUMPI

169 PUSH1 00

171 DUP1

172 REVERT

173 JUMPDEST

174 POP

175 PUSH2 0070

178 PUSH2 00f5

181 JUMP

182 JUMPDEST

183 PUSH1 40

185 DUP1

186 MLOAD

187 SWAP2

188 DUP3

189 MSTORE

190 MLOAD

191 SWAP1

192 DUP2

193 SWAP1

194 SUB

195 PUSH1 20

197 ADD

198 SWAP1

199 RETURN

200 JUMPDEST

201 CALLVALUE

202 DUP1

203 ISZERO

204 PUSH2 008e

207 JUMPI

208 PUSH1 00

210 DUP1

211 REVERT

212 JUMPDEST

213 POP

214 PUSH2 0070

217 PUSH20 ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

238 PUSH1 04

240 CALLDATALOAD

241 AND

242 PUSH2 00fb

245 JUMP

246 JUMPDEST

247 CALLVALUE

248 DUP1

249 ISZERO

250 PUSH2 00bc

253 JUMPI

254 PUSH1 00

256 DUP1

257 REVERT

258 JUMPDEST

259 POP

260 PUSH2 00e1

263 PUSH20 ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

284 PUSH1 04

286 CALLDATALOAD

287 AND

288 PUSH1 24

290 CALLDATALOAD

291 PUSH2 0123

294 JUMP

295 JUMPDEST

296 PUSH1 40

298 DUP1

299 MLOAD

300 SWAP2

301 ISZERO

302 ISZERO

303 DUP3

304 MSTORE

305 MLOAD

306 SWAP1

307 DUP2

308 SWAP1

309 SUB

310 PUSH1 20

312 ADD

313 SWAP1

314 RETURN

315 JUMPDEST

316 PUSH1 00

318 SLOAD

319 SWAP1

320 JUMP

321 JUMPDEST

322 PUSH20 ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

343 AND

344 PUSH1 00

346 SWAP1

347 DUP2

348 MSTORE

349 PUSH1 01

351 PUSH1 20

353 MSTORE

354 PUSH1 40

356 SWAP1

357 SHA3

358 SLOAD

359 SWAP1

360 JUMP

361 JUMPDEST

362 PUSH1 00

364 PUSH20 ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

385 DUP4

386 AND

387 ISZERO

388 ISZERO

389 PUSH2 0147

392 JUMPI

393 PUSH1 00

395 DUP1

396 REVERT

397 JUMPDEST

398 CALLER

399 PUSH1 00

401 SWAP1

402 DUP2

403 MSTORE

404 PUSH1 01

406 PUSH1 20

408 MSTORE

409 PUSH1 40

411 SWAP1

412 SHA3

413 SLOAD

414 DUP3

415 GT

416 ISZERO

417 PUSH2 0163

420 JUMPI

421 PUSH1 00

423 DUP1

424 REVERT

425 JUMPDEST

426 POP

427 CALLER

428 PUSH1 00

430 SWAP1

431 DUP2

432 MSTORE

433 PUSH1 01

435 PUSH1 20

437 DUP2

438 SWAP1

439 MSTORE

440 PUSH1 40

442 DUP1

443 DUP4

444 SHA3

445 DUP1

446 SLOAD

447 DUP6

448 SWAP1

449 SUB

450 SWAP1

451 SSTORE

452 PUSH20 ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff

473 DUP6

474 AND

475 DUP4

476 MSTORE

477 SWAP1

478 SWAP2

479 SHA3

480 DUP1

481 SLOAD

482 DUP4

483 ADD

484 SWAP1

485 SSTORE

486 SWAP3

487 SWAP2

488 POP

489 POP

490 JUMP

491 STOP

492 LOG1

493 PUSH6 627a7a723058

500 SHA3

501 INVALID

502 INVALID

503 SWAP10

504 DELEGATECALL

505 GASLIMIT

506 SWAP7

507 TIMESTAMP

508 DUP8

509 INVALID

510 INVALID

511 INVALID

512 SWAP4

513 LOG4

514 SWAP1

515 JUMPI

516 INVALID

517 CALLVALUE

518 INVALID

519 BLOCKHASH

520 INVALID

521 SWAP2

522 INVALID

523 INVALID

524 INVALID

525 INVALID

526 CALLCODE

527 SWAP13

528 DUP9

529 INVALID

530 INVALID

531 RETURN

532 INVALID

533 STOP

534 INVALID

535 STOP

536 STOP

537 STOP

538 STOP

539 STOP

540 STOP

541 STOP

542 STOP

543 STOP

544 STOP

545 STOP

546 STOP

547 STOP

548 STOP

549 STOP

550 STOP

551 STOP

552 STOP

553 STOP

554 STOP

555 STOP

556 STOP

557 STOP

558 STOP

559 STOP

560 STOP

561 STOP

562 STOP

563 STOP

564 STOP

565 INVALID

566 LTALL THE OPCODES OF THE CONTRACT CAN BE SEEN BETTER HERE: https://solmap.zeppelin.solutions/

The first instructions can be ignored, but at instruction 11 we find our first JUMPI. If it doesn’t jump, it will continue through instructions 12 to 15 and end up in a REVERT, which would halt execution. But if it does jump, it will skip these instructions to the location 16 (hex 0x0010, which was pushed to the stack at instruction 8). Instruction 16 is a JUMPDEST.

Keep on stepping through the opcodes until the Transaction slider is all the way to the right. A lot of blah-blah just happened, but only in location 68 do we find a RETURN opcode (and a STOP opcode in instruction 69, just in case). This is rather curious. If you think about it, the control flow of this contract will always end at instructions 15 or 68. We’ve just walked through it and determined that there are no other possible flows, so what are the remaining instructions for?

The set of instructions we’ve just traversed (0 to 69) is what’s known as the “creation code” of a contract. It will never be a part of the contract’s code per se, but is only executed by the EVM once during the transaction that creates the contract. As we will soon discover, this piece of code is in charge of setting the created contract’s initial state, as well as returning a copy of its runtime code. The remaining 497 instructions (70 to 566) which, as we saw, will never be reached by the execution flow, are precisely the code that will be part of the deployed contract.

If you open the deconstruction diagram: https://cdn.rawgit.com/ajsantander/23c032ec7a722890feed94d93dff574a/raw/a453b28077e9669d5b51f2dc6d93b539a76834b8/BasicToken.svg You should see how we’ve just made our first split: we’ve differentiated creation-time vs. runtime code.

This is the most important concept of this part: The creation code gets executed in a transaction, which returns a copy of the runtime code, which is the actual code of the contract. As we will see, the constructor is part of the creation code, and not part of the runtime code. The contract’s constructor is part of the creation code; it will not be present in the contract’s code once it is deployed.

Let’s re-take our top-down approach, this time understanding all the instructions as we go along, not skipping any of them. First, let’s focus on instructions 0 to 2, which use the PUSH1 and MSTORE opcodes.

PUSH1simply pushes one byte onto the top of the stack.MSTOREgrabs the two last items from the stack and stores one of them in memory:

mstore(0x40, 0x80)

| |

| What to store.

Where to store.

(in memory)

This basically stores the number 0x80 (decimal 128) into memory at position 0x40 (decimal 64). We will see why later.

You might be wondering: what happened to instructions 1 and 3? PUSH instructions are the only EVM instructions that are actually composed of two or more bytes. So, PUSH 80 is really two instructions. The mystery is revealed, then: instruction 1 is 0x80 and instruction 3 is 0x40.

Here we have a bunch of new opcodes: CALLVALUE, DUP1, ISZERO, PUSH2, and REVERT.

CALLVALUEpushes the amount of wei involved in the creation transaction.DUP1duplicates the first element on the stack.ISZEROpushes a 1 to the stack if the topmost value of the stack is zero.PUSH2is just like PUSH1 but it can push two bytes to the stack instead of just one.REVERThalts execution.

So what’s going on here? In Solidity, we could write this chunk of assembly like this:

if(msg.value != 0) revert();

This code was not actually part of our original Solidity source, but was instead injected by the compiler because we did not declare the constructor as payable. In the most recent versions of Solidity, functions that do not explicitly declare themselves as payable cannot receive ether.

Going back to the assembly code, the JUMPI at instruction 11 will skip instructions 12 through 15 and jump to 16 if there is no ether involved. Otherwise, REVERT will execute with both parameters as 0 (meaning that no useful data will be returned).

Thsi involves instructions between the 16th to the 37th as we can see here:

- The first four instructions (17 to 20):

MLOAD 40reads whatever is in memory at position 0x40 and pushes that to the stack.

MLOAD (X): Reads on memory from position X to x+32 (Remember is a 256-bit VM) If you recall from a little earlier, that should be the number 0x80 we stored on the Free memory pointer section. On the following instructions we find:

-

PUSH 0x20(decimal 32) to the stack (instruction 21). -

DUP1(instruction 23) copies the value to the nth position of the stack starting by the top. -

PUSH 0x0217(decimal 535) (instruction 24). -

DUP4Finally duplicates the fourth value (instruction 27), which should be0x80again. -

On instruction 28, CODECOPY is executed, which takes three arguments: target memory position to copy the code to, instruction number to copy from, and number of bytes of code to copy.

CODECOPY(t, f, s): Copysbytes from code at positionfto mem at positiontSo, in this case, it targets memory at position 0x80, from byte position 535 in code, 32 bytes of code length. Remember that on the stack we have now: 0x20 (32, the DUP1 one) < 0x0217 (535 as dec PUSH) < 0x80 (DUP4 value copied). Then it has been taken as inputs for CODECOPY OPCODE.

If you look at the entire disassembled code, there are 566 instructions. So why is this code trying to copy the last 32 bytes of code? Actually, when deploying a contract whose constructor contains parameters, the arguments are appended to the end of the code as raw hex data. In this case, the constructor takes one uint256 parameter, so all this code is doing is copying the argument to memory from the value appended at the end of the code. These 32 instructions don’t make sense as disassembled code, but they do in raw hex: 0x0000000000000000000000000...0000000000000000000002710. Which is, of course, the decimal value 10000 we passed to the constructor when we deployed the contract!

The next set of instructions (29 to 35) will be treated here and will resolve the first Free Memory Pointer section. This are the instructions involved:

029 DUP2

030 ADD

031 PUSH1 40

033 SWAP1

034 DUP2

035 MSTOREDUP2Copies the 2nd item of the stack, which is 0x40 if you remember, and copies it on the top of the stack.ADD(x, y)just doesx + yADDhere adds 0x80 plus 0x20 (Note that were the two Top elements of the Stack. 0x80 came from de DUP4 of last section and 0x20 from the DUP2 of this section) (This explanation should help to understand the stack situation). ThisADDoperation caries us to the number0xa0: that is, they offset the value by 0x20 (32) bytes. Now we can start making sense of instructions 0 to 2 of the Free Memory pointer.

Solidity keeps track of something called a “free memory pointer”: that is, a place in memory we can use to store stuff, with the guarantee that no one will overwrite it (except us if we make a mistake, of course, using inline assembly or Yul).

So, since we stored the number 10000 in the old free memory position, we updated the free memory pointer by shifting it 32 bytes forward.

We know now that "free memory pointer" or the code mload(0x40, 0x80). is just like say: “We’ll be writing to memory from this point on and keeping a record of the offset, each time we write a new entry.” Every single function in Solidity, when compiled to EVM bytecode, will initialize this pointer.

What’s in memory between 0x00 to 0x40, you may wonder. Nothing. It’s just a chunk of memory that Solidity reserves for calculating hashes, which, as we’ll see soon, are necessary for mappings and other types of dynamic data.

Now, on instruction 37, MLOAD reads from memory at position 0x40 (pushed on the instruction 36) and basically downloads our 10000 value from memory into the stack, where it will be fresh and ready for consumption in the next set of instructions.

This is a common pattern in EVM bytecode generated by Solidity: before a function’s body is executed, the function’s parameters are loaded into the stack (whenever possible), so that the upcoming code can consume them — and that’s exactly what’s going to happen next.

Here we will continue with instructions from 38 to 55.

These instructions are nothing more and nothing less than the constructor’s body: that is, the Solidity code:

totalSupply_ = _initialSupply;

balances[msg.sender] = _initialSupply;The first four instructions are pretty self-explanatory (38 to 42).

- First,

0is pushed to the stack. - Then the second item in the stack is duplicated (that’s our 10000 number).

- Then the number

0is duplicated and pushed to the stack, which is the position slot in storage oftotalSupply_. - Now,

SSTOREcan consume the values and still keep 10000 lying around for future use:

SStore(p, v) -> storage[p] := v Another way of explaining it will be:

SSTORE(0x00, 0x2710)

| |

| What to store.

Where to store.

(in storage)

We have just stored the number 10000 in the variable totalSupply_.

The next set of instructions (43 to 54) are a bit disconcerting, but will basically deal with storing 10000 in the balances mapping for the key of msg.sender.

Before looking at the instructions, we must see how mappings are stored on storage.

Statically-sized variables (everything except mapping and dynamically-sized array types) are laid out contiguously in storage starting from position 0. Multiple items that need less than 32 bytes are packed into a single storage slot if possible, according to the following rules:

-

The first item in a storage slot is stored lower-order aligned.

-

Elementary types use only that many bytes that are necessary to store them.

-

If an elementary type does not fit the remaining part of a storage slot, it is moved to the next storage slot. (This is what causes problems with memmory optimisation, and an example of why we need to write in Solidity thinking always about what the compiler will do.)

-

Structs and array data always start a new slot and occupy whole slots (but items inside a struct or array are packed tightly according to these rules).

Important Warning of the documentation here!

When using elements that are smaller than 32 bytes, your contract’s gas usage may be higher. This is because the EVM operates on 32 bytes at a time. Therefore, if the element is smaller than that, the EVM must use more operations in order to reduce the size of the element from 32 bytes to the desired size.

It is only beneficial to use reduced-size arguments if you are dealing with storage values because the compiler will pack multiple elements into one storage slot, and thus, combine multiple reads or writes into a single operation. When dealing with function arguments or memory values, there is no inherent benefit because the compiler does not pack these values.

Finally, in order to allow the EVM to optimize for this, ensure that you try to order your storage variables and struct members such that they can be packed tightly. For example, declaring your storage variables in the order of uint128, uint128, uint256 instead of uint128, uint256, uint128, as the former will only take up two slots of storage whereas the latter will take up three.

Now we have to talk about the rest of variables:

Due to their unpredictable size, mapping and dynamically-sized array types use a Keccak-256 hash computation to find the starting position of the value or the array data. These starting positions are always full stack slots.

The mapping or the dynamic array itself occupies an (unfilled) slot in storage at some position p according to the above rule (or by recursively applying this rule for mappings to mappings or arrays of arrays).

-

For a dynamic array, this slot stores the number of elements in the array (byte arrays and strings are an exception here, see below).

-

For a mapping, the slot is unused (but it is needed so that** two equal mappings after each other will use a different hash distribution)**.

-

Array data is located at

keccak256(p)and. -

The value corresponding to a mapping key

kis located atkeccak256(k . p)where . is concatenation. If the value is again a non-elementary type, the positions are found by adding an offset ofkeccak256(k . p). -

Bytesandstringstore their data in the same slot where also the length is stored if they are short. In particular: If the data is at most 31 bytes long, it is stored in the higher-order bytes (left aligned) and the lowest-order byte stores length * 2. If it is longer, the main slot stores length * 2 + 1 and the data is stored as usual in keccak256(slot).

Movig to the instructions (43 to 54) again, we can see the CALLER Opcode.

Now we know that we need to store a mapping, then, looking avobe we can conclude...???

Long story short, it will concatenate the slot of the mapping value (in this case the number 1, because it’s the second variable declared in the contract) with the key used (in this case, msg.sender, obtained with the opcode CALLER), then hash that with the SHA3 opcode and use that as the target position in storage. Storage, in the end, is just a simple dictionary or hash table.

CALLER-> sender (excluding delegatecall)

- So it puts the sender address (I guess) on the top of the stack.

- Then

DUP2dublicates a0x0and puts it on top of the stack. - Finally, we find the

MSTOREwhere address of the sender is saved on the position0of the memory. (We already saw that this is a common practice on the evm.) - Then

0x01is pushed on the top of the stack. - Also

0x20which is 32 in dec is pushed on the top of the stack. - Then we see

MSTOREagain saving in memory0x01on position0x20(32). - Now appears a new Opcode called

SWAPnand reorders the stak leaving on the top the0x2710(10000 of the input) - Finally, the

SHA3opcode calculates the Keccak256 hash of whatever is in memory from position 0x00 to position 0x40 — that is, the concatenation of the mapping’s slot/position with the key used (As we saw on the section avobe, that's how Solidity stores mappings). This is precisely where the value 10000 will be stored in our mapping:

SSTORE(hash..., 0x2710)

| |

| What to store.

Where to store.

SHA3-> Calculates the Keccak256 hash of whatever is in memory from position 0x00 to position 0x40.SSTORE(x, y)-> Storage[p] := v, or, store y on x.SWAPn-> Swap topmost and nth stack slot below it.

And that’s it. At this point, the constructor’s body has been fully executed.

In instructions 56 to 65, we’re performing a code copy again. Only this time, we’re not copying the last 32 bytes of the code to memory; we’re copying 0x01d1 (decimal 465) bytes starting from position 0x0046 (decimal 70) into memory at position 0.

We can see it analyzing the stack:

PUSH2pushed 2 bytes to the top of the stack:0x01d1(465 dec).DUP1duplicated the0x01d1value (I don't know why because it already was on the top because of thePUSH2).PUSH2pushed0x0046(70 dec) to the top of the stack.PUSH1pushed a0x00byte to the top of the stack.CODECOPYopcode was executed doing the following:

CODECOPY(0x00,0x46,0x01d1)

| | |

| | Ammount of bytes to copy.

| Instruction/Position to start copy code.

Position to copy on memory.

The runtime bytecode is contained in those 465 bytes. This is the part of the code that will be saved in the blockchain as the contract’s runtime code, which will be the code that will be executed every time someone or something interacts with the contract.

What instructions 66 to 69 do? The code that we copied to memory is returned because of them.

RETURN(p, s) -> End execution, return data mem[p...(p+s))

RETURN grabs the code copied to memory and hands it over to the EVM. If this creation code is executed in the context of a transaction to the 0x0 address, the EVM will execute the code and store the return value as the created contract’s runtime code.

That’s it! By now, our BasicToken contract instance will be created and deployed with its initial state and runtime code ready for use. But, to which addres??

The address for an Ethereum contract is deterministically computed from the address of its creator (sender) and how many transactions the creator has sent (nonce). The sender and nonce are RLP encoded and then hashed with Keccak-256. The result ends being the address of the contract.

See that all the EVM bytecode structures we analyzed are generic, except the one highlighted in purple:

If you look at the deconstruction diagram, we’re going to start by looking at the second big split block titled BasicToken.evm (runtime).