| title | description | authors | pubDate | heroImage | tags | featured | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mini.WebVM: Your own Linux box from Dockerfile, virtualized in the browser via WebAssembly |

WebVM is a Linux-like virtual machine running fully client-side in the browser. It is based on CheerpX: a x86 execution engine in WebAssembly by Leaning Technologies. With today’s update, you can deploy your own version of WebVM by simply forking the repository on GitHub and editing the included Dockerfile. A GitHub Actions workflow will automatically deploy it to GitHub pages.

|

|

May 22 2023 |

/blog/blog-banners/webvm-post.png |

|

true |

TLDR: WebVM is a Linux-like virtual machine running fully client-side in the browser. It is based on CheerpX: a x86 execution engine in WebAssembly by Leaning Technologies. With today’s update, you can deploy your own version of WebVM by simply forking the repo on GitHub and editing the included Dockerfile. A GitHub Actions workflow will automatically deploy it to GitHub pages.

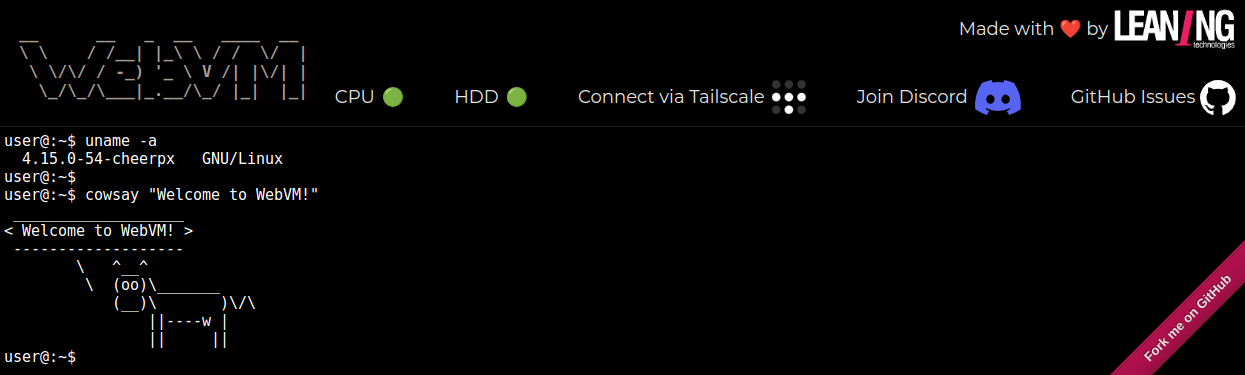

WebVM is a full Debian-based Linux environment running client-side in the browser. It is based on CheerpX, a x86 virtualization technology powered by a WebAssembly JIT engine.

WebVM’s initial announcement, around one year ago, generated lots of attention from the community. The same happened again with the update that followed, introducing support for networking. Needless to say, we have been overjoyed and somewhat overwhelmed by this positive response.

We now want to move one step forward, by allowing the community to use this technology without restrictions. Today we are releasing Mini.WebVM, a simplified integration that makes it possible for anybody to customize and deploy their own version of WebVM via GitHub pages or any other hosting, with no more than a couple of clicks.

WebVM is a Linux-like environment running fully client side in the browser. This is made possible by combining:

- CheerpX: A state-of-the-art x86-to-WebAssembly virtualization engine. CheerpX can performantly and securely run unmodified x86 binaries in the browser via an advanced execution engine. The engine JIT-compiles WebAssembly modules from x86 binary code in real time. Runtime generated code and self-modifying code are fully supported.

- Ext2 disk images: A robust file system format natively supported by CheerpX. It provides high performance access to complete Linux setups over an HTTP backend. In the case of WebVM, the image is populated with Debian and comes with many packages already installed, including python, nodejs, gcc, clang, curl, etc. Disk chunks are downloaded on-demand, to minimize bandwidth usage and boot time.

- In-browser networking: Thanks to a Tailscale integration, you can connect WebVM to your own tailnet and enjoy bidirectional networking to and from the virtual machine. Traffic is encrypted via Tailscale and fully private.

- Xterm.js: A full fledged terminal emulator in the browser. It makes it possible to use not just simple command line tools but full TUIs as well.

While the initial releases of WebVM received tremendous interest from the community, it was clear that something was missing. The most common feedback we received was: “This is cool, but how can I use it for my own project?”

It took us a few months, but we believe we have now identified and fixed all the friction points to make CheerpX and WebVM finally usable.

Both CheerpX and WebVM are just a collection of static files. There is no backend component besides an HTTP server.

Still, due to a few technical requirements it was practically quite difficult to allow any customized deployment of WebVM.

- SharedArrayBuffer and Cross-Origin Isolation: One of WebAssembly’s unique features is the capability for real multi-threaded execution via Web Workers and SharedArrayBuffer. Unfortunately, due to egregious CPU vulnerabilities, this feature is only enabled via a set of special HTTP headers (COEP/COOP/CORP) guaranteeing Cross-Origin isolation. We know from experience that this (over)complicated setup is difficult to get right, and failures are tricky to debug. Moreover, it could effectively be impossible to set these headers if the user does not control the server configuration, which is common in hosted scenarios.

- Ext2 image creation: Historically our process for populating the system image was completely manual, using `dd` and `mk2efs` to initialize the filesystem and `debootstrap` to initialize the distro. All of this is quite normal for people with experience in Linux administration, but unusual (to say the least) in the context of a Web application. This whole setup was even error-prone for us, with no guarantees that images could be generated consistently at any point in time.

- Ext2 image deployment: We knew that some form of chunk-based, on-demand access was necessary, since any Debian setup of practical use would require at least several hundred MB. Our original plan involved using HTTP byte ranges, to download chunks dynamically, and standard HTTP compression for bandwidth efficiency. As crazy as it might sound, this combination of standard HTTP features is not possible. The reason is a fundamental ambiguity: is the requested byte range part of the compressed or uncompressed data? The only viable solution we found has been to use a reverse-proxy hack on our origin server. Needless to say this solution could never be compatible with a user-friendly deployment model.

Our solution to all these problems has been to fully embrace the capabilities of GitHub, in particular GitHub Actions and GitHub Pages.

- SharedArrayBuffer and Cross-Origin Isolation: GitHub Pages do not enable COEP/COOP/CORP headers, but the problem can be solved by automatically loading a service worker that injects the headers as required. The same setup works transparently on any other hosting as well.

- Ext2 image creation: we standardized the definition of the image via Dockerfile, with the conversion to Ext2 happening via a GitHub Actions workflow. Dockerfiles also simplify supporting alternative distributions and adding use-case specific binaries, for example by compiling them as part of the Docker build process. As a side effect, all images are now reproducible.

- Ext2 image deployment: After multiple attempts, we accepted that the right choice was to use pure HTTP byte ranges. This implies accepting the loss of bandwidth efficiency since, as mentioned before, we cannot enable HTTP compression at the same time. In exchange, we can achieve a frictionless deployment, since now any HTTP server works just fine. In particular, we can automatically deploy to GitHub Pages via the same workflow that creates the Ext2 image in the first place. Or, should I say, that was the original plan.

As we prepared this announcement, we started noticing extremely unsatisfactory performance on first loads of newly forked deployment.

As far as we can see, the Fastly CDN sits in front of GitHub page domains, which allows very quick responses to CDN-cached requests. However, its behavior on uncached data is not quite as good.

We believe that Fastly is currently poorly configured on GitHub Pages, in particular the “ Streaming Miss” feature might not be enabled. Due to this, when the first 128KB chunk of the disk is requested, Fastly downloads instead the whole 600MB image from the underlying server. Only after the full download is completed can the originally requested range be returned. The GitHub upstream HTTP server seems to be not very performant to begin with and the whole download can easily take up to a minute!

As much as we care about elegant solutions, we care more about the performance of the end results. To work around this problem, we modified the GitHub Actions workflow to pre-process the image into individual chunks, which can now be downloaded separately. This is fully transparent to the user, and makes it possible to achieve satisfactory loading times on first access.

Thanks to these improvements it is now possible to fork and customize WebVM in an exceptionally streamlined manner. Just enable GitHub Pages for your fork and deploy using the provided GitHub Action workflow. You can modify the Dockerfile as you wish to include your favorite packages or your own project and immediately see it running in the browser.

The WebVM repository is on GitHub, and includes step-by-step instructions to deploy your own Mini.WebVM:

A reference deployment is available on https://mini.webvm.io:

The biggest pain point remains accessing large filesystem images exclusively with Web standards. It seems to be one of those problems where most of the pieces for a great solution are in place, but somehow they cannot fit together.

GitHub Pages in particular have a total allowed size of 1GB for the whole site, which is more than enough to demonstrate the capabilities of WebVM, but a serious limitation for production use. When hosting elsewhere, the image size can be up to 2GB; the limit in this case is caused by range headers being parsed as 32-bit signed integers. While this is suboptimal, it is likely that practical use cases could be built in this scenario.

To the best of our knowledge, to go beyond the 2GB limit (and to drastically improve bandwidth efficiency via compression) will require a custom backend, although a small edge computing solution could probably work as well. We plan to extend WebVM to easily support hundreds of GBs (and possibly more) in the future and we expect filesystem hosting, deployment and persistent storage support to be part of the commercial offering we will build around this product.

WebVM is based on a CheerpX build that we host. We encourage users to deploy their own versions of WebVM, but we don’t currently allow self-hosting of the CheerpX engine itself. This public build of CheerpX is provided as-is and is free to use for technological exploration, testing and non-commercial uses. If you want to build a product on top of CheerpX/WebVM, please get in touch: sales@leaningtech.com

Mini.WebVM is centered around ease-of-use and designed to unleash the creative power of the community around our technology. But we have certainly not stopped moving the technology forward.

Work is well underway for our next big release, booting a whole desktop environment in the browser. And, later in the year, running Windows applications and games using WINE.

Stay tuned for further updates. For any question, join us on Discord, or get in touch on Twitter.

For more information: