Here is a test script (taken from the Nightwatch.js homepage):

module.exports = {

'Demo test Google' : function (client) {

client

.url('http://www.google.com')

.waitForElementVisible('body', 1000)

.assert.title('Google')

.assert.visible('input[type=text]')

.setValue('input[type=text]', 'rembrandt van rijn')

.waitForElementVisible('button[name=btnG]', 1000)

.click('button[name=btnG]')

.pause(1000)

.assert.containsText('ol#rso li:first-child', 'Rembrandt - Wikipedia')

.end();

}

};The characteristics of these tests is that they emulate what a manual tester would do. Whilst automating repetitive manual tasks is a good idea, it’s easy to forget that a human tester is able to adapt to common sense whereas a test script is dumb! You can see in the script above there are references to the HTML markup everywhere. This means if the HTML changes on that page as part of a small enhancement or restyle, the test script will fail.

Your immediate reaction might be that you can improve this script by doing some or all of the following:

- Remove dependency on the HTML structure

- Replace the

pausewithwaitForXXX - Extract the text to a resource file

- Employ a page-object pattern

These are all good measures for sure for fixing the problem with the test-script, but they are not fixes for the problem of test-scripts themselves - they are actually the problem!

Test scripts come AFTER you have finished coding as an after-thought. They are the shrink-wrap around your code. They can be a lot of fun to write when you first start out but the sad truth is, you are building up a steaming pile of technical-debt and you're unaware of it. As the pressure to release new features increases, these test scripts become a hindrance since they an after-thought and are almost always out of date. The higher your test-script coverage, the more likely it is that valid code changes will break the tests. Let's just say that one more time: "valid code changes will break the tests". This is where the false negatives appear and invariably, the tests are disabled "temporarily" (usually with the best intentions!)

Test scripts are not all bad, they can be useful. For example, you might want to start writing tests scripts before you refactor a legacy system, and replace the scripts as you write a the new system, or manual testers can use a record-playback tool to create a reproducible bug report for developers. Perhaps you have some non-technical testers and they maintain their own test scripts to help them speed up their current job, but they know to throw away the scripts as they become out-of-date and these scripts do not block a build. Notice the common thread amongst all the use-cases and problems for test scripts, is that they are temporary and short-lived.

Test scripts temporary and short-lived. Remember that, always!

Also notice how the script tells you HOW the system is doing something through clicking and pressing, but not WHAT or WHY. It completely lacks context. The interesting thing here, is that there were specifications at some point that specified how the system should behave. Someone, somewhere talked, sent emails, looked at wire-frames and whiteboards and transformed a lot of specifications into code. But where is the specification kept? In a GitHub issue? In the brains of the developers that wrote it years ago? Actually, it's in the code - that's always the source of truth.

Now let's look at an executable specification in contrast, and let's assume we are Google, staying true to the example above:

Feature: Google Index updates cached pages

As a searcher

I want to see up to date results

So that I can find the information I am looking for

Scenario: User searches after the index

Given Wikipedia contains a page with the title "Rembrandt"

And Google has indexed the Wikipedia site

When a user searches for the term "rembrandt van rijn"

Then the results show "Wikipedia - Rembrandt"That is the specification right there. It does not tell you at all HOW to do it, but does tell you WHAT and WHY. From the specifications, you can do two things:

- Write automated tests that check the code fulfils the specifications

- Write the actual code that fulfils the specifications.

You can even do this crazy thing called Test Driven Development (TDD) that drive the development of the specs above using tests and is known to reduce defects by 30-50%.

The tests produced in this fashion are always long lasting because they come BEFORE the code. Think about it, every time you want to change the code, you start by changing the specs, and then you go on to change the tests as well as the code to match. So you have three artifacts: the specs, the tests and the code. Some frameworks merge the specs and the code (like Mocha and Jasmine) and others separate them (like Cucumber). The example above shows Cucumber's Gherkin syntax, and you can achieve the same with Mocha/Jasmine like this:

describe('Google Index updates cached pages', function() {

// As a searcher

// I want to see up to date results

// So that I can find the information I am looking for

it('User searches after the index', function() {

// Given Wikipedia contains a page with the title "Rembrandt"

// And Google has indexed the Wikipedia site

// When a user searches for the term "rembrandt van rijn"

// Then the results show "Wikipedia - Rembrandt"

});

});When you use feature files to write test scripts, you are making one of the most common mistakes when it comes to writing a maintainable set of executable specifications. In addition to suffering every single problem mentioned in Lesson #1, there are an additional set of gotchas when using Gherkin in this fashion. Let's explore why it's a terrible idea!

There's something very appealing about feature files that look like this:

Given I visit "google.com"

Then the title should be Google

And the text input should be visible

When I set the the text input value to "rembrandt van rijn"

And I click the "btnG" button

And I wait 1 second

Then the first list item child should be "Rembrandt - Wikipedia" The attractive aspects seem to be the readability and the step reuse. These are highly desirable qualities of any codebase, however the language used in these feature files is not a programming language, it is a language intended to express the business domain and therefore it is the domain language. Tools like Cucumber contain a natural language parser that helps you to extract meaning out of this domain language, but you are not forced to use a specific structured syntax like you have to when programming. Developers see this as an "opportunity" to create structured test scripts, but they end up missing the point of domain language entirely. Worse yet, they plant the slow germinating seeds of their worst maintenance nightmare!

If you are not familiar with the meaning of the "domain" in the context of software engineering, you would be wise to research the subject starting with the Wikipedia page.

Features files with plain language scenarios and steps are intended to discover and iterate over the domain of your application. The domain language evolves with time. It evolves as the application code is written to fulfil the specifications, and through new discoveries that are made whilst working with customers. The language becomes more specific and less ambiguous and most importantly, the domain language gets used everywhere. It's used in the specifications, in the test code and in the application code. It's even the language the customer sees. All of this is to say, the domain language becomes ubiquitous, or to use the correct buzzwords, it is the ubiquitous domain language.

The ubiquitous domain language is the point of natural language executable specifications. When correctly used in this way, tools like Cucumber suit their purpose very well. However, when you write test scripts using Cucumber's Gherkin syntax, it's like writing your application using Regex! It's possible, but it's not going to be fun to maintain. The Gherkin syntax is not easy to refactor and if you change your step implementations, you need to update in multiple places. For domain concerns, this is not a big issue since reuse means you have got some part of your domain figured out and therefore it's unlikely that you'll make huge changes. For example "Given I have created an account". More over, if you ever change the implementation of how an account is created, you would only change the test and the code underneath the specification but not the specification itself. When the Gherkin is syntax used for UI tests however, changing the implementation of the account creation would mean updating all the scripts that reference the UI to create an account. I told you it's a terrible idea!

To put it succinctly, using UI based steps in your specification breaks the ubiquitous language principle entirely and entirely defeats the purpose. If you are interested in step reuse and the readability of your testing codebase, you can achieve that through proper software engineer principles at the automation layer, thus creating a clear delineation between the natural domain language, and the test automation code that verifies the domain language is being fulfilled by the application.

If however you insist on writing test scripts and wish to ignore all the advice, you should not use an executable specification tool like Cucumber. You would be better off removing the natural language parsing and instead, apply some good software engineering tools and concepts to create some code that you have complete control over. Something like this would be better for you:

client

.visit('google.com')

.getTitle().should.be('Google')

.type('rembrandt van rijn')

.clickThe('Search', 'button')

.wait(aSecond)

.expect(theFirstItem).to.be('Rembrandt - Wikipedia');Now, repeat after me: "I will never ever write test script using Gherkin again, never ever!". Say it 10 times.

You've probably heard of unit and end-to-end testing, and perhaps you have a clear distinction between integration and acceptance tests in your mind. Unfortunately, there is not a widely accepted set of definitions for the different test types, and they vary from team to team. One definition everyone can agree on is that of a unit test: When a System Under Test (SUT) is a single unit of code, like a function in JavaScript, the test that exercises that SUT is a unit test. However when we get into integration tests vs service tests vs acceptance tests vs end-to-end tests, the dichotomy is blurred.

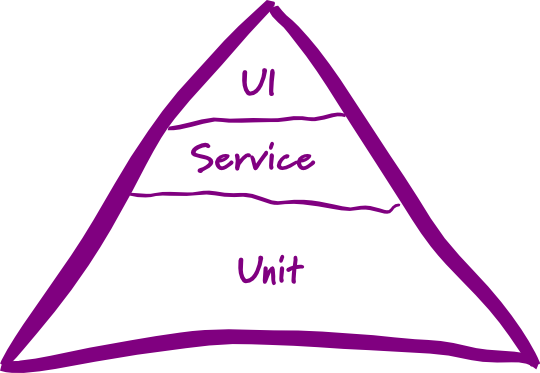

This is a problem when you're trying to adhere to the testing pyramid as it can be difficult to understand what the middle and top layers really mean. If look at this Google image search, you'll see a plethora of opinions about the contents and order above the bottom layer, which is always unit tests.

For the record, this is the most correct one in our opinion, as originally posted by Mike Cohn in his article The Forgotten Layer of the Test Automation Pyramid:

In this diagram, the top layer refers to any test that exercises the SUT through the UI. This is not the same as UI unit tests which actually belong in the bottom layer. This is an important distinction as UI unit tests are strongly encouraged, and with technologies such as React are easier than ever to test.

Notice how the middle layer is called "Service". This tells us that tests at this level should exercise the service layer. The service layer exposes business functions in a system, such as shipOrder for an eCommerce site and transferMoney for a bank system.

These business functions will typically operate on domain entities. Domain entities are objects with a conceptual identity in a business context. For example, the transferMoney service would take money from one AccountHolder (conceptual identity), and transfer to another AccountHolder entity. This is what Domain Driven Design (DDD) is all about, and you would be wise to learn about this approach (Wikipedia is a good start).

Of course, you still write unit tests for all the services and the domain objects, which means there's a very specific test left to do, and that is to test the domain integrity. The domain integrity answers questions like: does the transferMoney service work with the AccountHolder domain entities?

You can imagine developing the transferMoney service with 100% unit test coverage, and the same for the "account holder". You then try your new transferMoney service and it works, so you ship it. A new developer comes along and writes a savingsAccount service. They refactor the AccountHolder and associated unit test to store the balance in a nested field checkingAccount.balance instead of balance. They run all the unit tests and they pass, even though the transferMoney service is still expecting the original balance field to in order to work. The developer is not interested in the original transferMoney service so they don't know to test it and they ship their new feature. A regression bug has just been introduced.

Service level tests are awesome at catching exactly these sorts of errors. Interestingly, you don't need to go out of your way to write extensive tests to cover these areas, this error-catching capability is a great side-effect of doing modelling by example (more coming soon).

So in summary, you can't expect units tests to work alone, you need service tests to make sure they work together. This picture illustrates this point perfectly:

If you imagine an application that has a completely speech based UI, then you can imagine simply talking to the system and it responding to you. For example, you might say "transferMoney from AccountHolder A to AccountHolder B" and it would respond with "Successfully completed transfer".

This is how you should look at your application domain, it is the underlying system that you can put any user-interface on top of. The UI can be a graphical one, or speech based and even haptic. The domain is the most important part of the software and the domain does not need Graphical User Interface. It might take a little getting used to, but it's one of those things that once you truly understand, you don't go back!

(taken from Taking Back BDD)

As mentioned in lesson #2, the domain is best tested as a service level tests. If you do test at the UI, you are introducing an additional layer that creates slowness. UI-based tests run in the magnitude of 1000x the speed of unit tests, and 100x the speed of service tests. UI tests that drive all the way to the domain are also brittle, not only in the sense of waiting for the right elements to appear and such, which you can actually deal with, but also in the sense of breaking whenever new changes to the UI are added.

With technologies like React, it's easier than ever to write unit tests for the UI components. When you also unit test the service and domain layers, you have a testing codebase that can a) run at lightning speed and b) prevent regression when making seemingly unrelated changes. The domain tests are the glue between all these units.

As you will see in this repository, some of the domain tests themselves go through the UI, and they are labeled as @critical. This means that these domain tests are part of the critical path for the functionality and we want to ensure the UI aspect works. They first run against the service layer, then the same tests run against the UI. This is how you get the perfect balance and adhere to the testing triangle.

If you test your domain through the UI only, then changes to your domain will be costly and over time, this sill mount up to a codebase you don't really enjoy changing. If you go mostly through the domain, but have just a few UI tests, you will profit!