作者: Deane Barker

出版社: O'Reilly Media

副标题: Systems, Features, and Best Practices

出版年: 2015-10-25

页数: 250

定价: USD 29.99

装帧: Paperback

ISBN: 9781491908129

- Web Content Management

- Part I. The Basics

- Part II. The Components of Content Management Systems

- CMS Feature Analysis

- Content Modeling

- Content Aggregation

- Editorial Tools and Workflow

- Output and Publication Management

- Other Features

How is content management any different from managing any other type of data? There are two key differences:

- Content is created differently.

- Content is used differently.

Content is created through “editorial process.” This process is what humans do to prepare information for publication to an audience. It involves modeling, authoring, editing, reviewing, approving, versioning, comparing, and controlling.

The creation of content pivots largely on the opinions of human editors:

- What should the subject of the content be?

- Who is the intended audience of the content?

- From what angle should the subject be approached?

- How long should the content be?

- Does it need to be supported by media?

Despite significant advances in computing, these are not decisions a computer will make.

The editorial process is iterative—content is rarely created once, perfectly, and then never touched again. Rather, content is roughed in and refined over and over like clay on a potter’s wheel, often even after being published. Content can change with the passage of time and the evolution of circumstance.

Content is constantly in some state of flux and turnover. It’s never “right.” It’s just “right now.”

Content is data we create for a specific purpose: to distribute it with the intention of it ultimately being consumed by other humans.

Content is an investment in the future, not a record of the past.

Bringing these two concepts together, we arrive at our best attempt at a concise definition:

Content is information produced through editorial process and ultimately intended for human consumption via publication.

Content is created and managed, then it is published and delivered.

A content management system (CMS) is a software package that provides some level of automation for the tasks required to effectively manage content.

Specifically, a CMS provides core control functions, such as:

- Permissions

- Who can see this content? Who can change it? Who can delete it?

- State management and workflow

- Is this content published? Is it in draft? Has it been archived and removed from the public?

- Versioning

- How many times has this content changed? What did it look like three months ago? How does that version differ from the current version? Can I restore or republish an older version?

- Dependency management

- What content is being used by what other content? If I delete this content, how does that affect other content? What content is currently “orphaned” and unused?

- Search and organization

- How do I find a specific piece of content? How do I find all content that refers to X? How do I group and relate content so it’s easier to manage?

Using content in more than one place and in more than one way increases its value. Some examples:

- A news article appears on its own page, but also as a teaser on a category page and in multiple “Related Article” sidebars.

- An author’s bio appears at the bottom of all articles written by that person.

- A privacy statement appears at the bottom of every page on a website.

In these situations, this information is not created every time in every location, but simply retrieved and displayed from a common location.

If our content is structured correctly, we can manipulate it to display in different formats, publish it to different locations, and rearrange it on the fly to serve the needs of our visitors more effectively:

- We can allow users to consume content in other formats, such as PDF or other ebook formats.

- We can automatically create lists and navigation (more generally, “content aggregations”—see Chapter 7) for our website.

- We can create multiple translations of content to ensure we deliver the language most appropriate to the current user.

- We can alter the content we publish in real time based on the specific behaviors and conditions exhibited by our visitors.

A CMS enables this by structuring, storing, examining, and providing query facilities around our content.

Editor efficiency is increased by a system that controls what type of content editors can and can’t add, what formatting tools are available to them, how their content is structured in the editing interface, how the editorial workflow and collaboration are managed, and what happens to their content after they publish.

A good CMS enables editors to publish more content in a shorter time frame (it increases “editorial throughput”), and to control and manage the published content with a lower amount of friction or drag on their process.

A CMS simply manages content, it doesn’t create content.

A CMS doesn’t “know” anything about marketing.

Editors have never seen a button on an editing interface that they didn’t want to press. The only way to limit this seems to be to remove as many editing options as possible.

Governance is primarily a human discipline. You are determining the processes and policies that humans will abide by when working with your content. The CMS is just a framework for enforcement.

To pay the bills, companies behind open source software operate on one or more of the following models:

- Consulting and integration

- No one knows the CMS better than the company that built it, and it’s quite common for vendors to integrate their own software from start to finish, or to at least provide some higher-level consulting services with which to assist customers in integrating it themselves.

- Freemium

- The basic software is free, but a paid option exists that allows access to more functionality, a larger volume of managed content, or scaling options, such as the ability to load-balance. Sometimes the free product is quite capable, and sometimes it’s just a watered-down trial version meant to steer users toward paying for the full product.

- Hosting

- Many vendors offer “managed hosting” platforms for the open source systems they develop. The purported benefit is a hosting environment designed specifically for that system, and/or system experts standing by in the event of hosting problems. Note that the actual value here is a bit questionable, as there’s rarely secret information known only to the vendor that allows it to tailor a hosting platform to one CMS over another. Any available performance enhancements or configuration tweaks could just as easily be implemented by a savvy customer. The value is often just peace of mind that an “expert” is in charge.

- Training and documentation

- Open source software often lacks in documentation, and developer bias can lead to idiosyncratic, API-heavy systems. For these reasons, professional training can be helpful. Many vendors will offer paid training options, either remote or in-person. Less commonly, some offer paid access to higher-quality documentation.

- Commercial licensing

- Depending on the exact license, changes to open source software might have to be publicly released back to the community. Some vendors will offer paid commercial licenses for their open source systems to allow organizations to ignore this requirement, close the source, and keep their changes to themselves.

- Support

- When community support falls short, professional support can be helpful, and some vendors will provide a paid support option, either on an annual subscription or a per-incident basis.

- Additional testing and QA

- Some vendors offer a paid version of the software that is subjected to a higher “enterprise” level of testing and QA. In these cases, the free or “community” version is presented as lightly tested and nonsupported, while the enterprise (paid) version is marketed as the only one suitable for more demanding implementations.

Here are the more common ways of determining pricing:

- By editor/user

- The system is priced by the number of editing users, either per seat or concurrent. More rarely, the system is priced by the number of registered public users, but this usually only applies to community or intranet/extranet systems where it’s expected that visitors will be registered.

- By server

- The system is priced by the number of servers on which it runs (or, less commonly, on the number of CPU cores). This is quite common as larger installations will require more servers, thus extracting a higher price tag. With decoupled systems where the delivery environment is separated from the repository environment, this can get confusing: Do you pay for repository servers or delivery servers? Or both?

- By site

- The system is priced by the number of distinct websites running on it. This can be blurred by the vagueness of what constitutes a “website.” If we move our content from “microsite.domain.com” to “domain.com/microsite,” are we still under the same website and license fee? What about websites with different domain names that serve the same content (branded affinity sites, for instance)? What about alternate domains for different languages (“en.domain.com” for English and “de.domain.com” for German)?

- By feature

- The system is priced by add-on packages installed in addition to the core. Almost every commercial vendor has multiple features or packages that can be added on to the base system in order to increase value and price. These range from ecommerce subsystems to marketing tools. Note that each one of these features might also be licensed by user, server, or site, making their prices variable as well.

- By content volume

- The system is priced by the amount of content under management. This is less common than other models, as the number of content objects managed is highly dependent on the implementation. For example, should you manage your blog comments? Or can you move them to a companion database (or external service, like Disqus) and reduce content volume by 80% or more?

With most vendors, those benefits are some combination of the following:

- On-demand support

- Upgrades and patches as they are released

- Free licenses for development or test servers

- License management, in the event you need to license new servers or sites

If you’re considering multitenant SaaS, several questions become important:

- Is it appropriate for your industry? SaaS systems tend to group by the vertical in which they serve. For instance, OmniUpdate traditionally services higher education and HubSpot specializes in smaller, marketing-heavy websites. This enables these vendors to develop features common to those industries that will be used by multiple tenants of their systems.

- How much control do you have over the system? To what extent can you integrate with other systems or inject your own business logic? Since these systems are multitenant, vendors are leery of allowing significant customization, lest this destabilize the larger system for other clients. Some vendors will offer a dedicated, “sandboxed” environment in which you have more control, but this raises the question of how you’re now any better off than you would be if you installed a CMS yourself.

- Who can develop the website? Some vendors might require that template development or other integration be performed by their own professional services groups. This is common in SaaS systems that grew out of the in-house CMS of a development shop. In some cases, the subscription fee to use the system is simply a minimal gateway to enable the vendor to generate professional services income.

- If you part ways with the vendor, what happens to your content? Can you export it? In what format? What about your templates, which contain all of your presentation logic? Can you get that information out? Vendors in all software genres are notorious for lock-in, in order to prevent customers from leaving. Wise customers will evaluate the process for leaving a vendor as a system feature like any other.

- Are you considering the CMS on its merits, or just because it’s SaaS? Don’t engage with a SaaS vendor solely because they offer their software as a service, especially if you’re not particularly fond of the software itself. If SaaS if what you want, there are numerous options to get a SaaS-like experience from software you might like much more.

There are several common justifications for this, including:

- An in-house CMS doesn’t require a license fee (clearly, this is rendered moot by open source options, but it’s still quite common in project justifications).

- You’ll be experts in the usage of the resulting system and will not have to suffer the learning curve for an existing system.

- You will only build the needed functionality, avoiding software bloat and unnecessary complication.

There are situations where it might be the right choice:

- When the content model—more on that in Chapter 6—is very specific to the organization. (If all you publish is cat videos, building a management platform might not be difficult.)

- When the management needs are very simple and future development plans are absolutely known to be limited

- When the CMS is built by heavily leveraging existing frameworks to avoid as much rework as possible (e.g., Symfony for PHP, Django for Python, Entity Framework and MVC for ASP.NET)

Primarily, members of the content management team can be divided into:

- Editors

- Site planners

- Developers

- Administrators

- Stakeholders

Editors are responsible for creating, editing, and managing the content inside the CMS.

All editors are not created equal, and they might have a wide variety of capabilities. How editors can be limited in their capabilities to refine their subroles:

- By section/branch/location

- Editors might be able to edit only a specific subset of content on the website, whether that be a section, a branch on the content tree (we’ll talk about trees in Chapter 7), or some other method of localization. They might have full control over content in that area (the press section, or the English department, for example), but no control over content in other areas.

- By content type

- Editors might be able to edit only specific types of content (we’ll talk much more about content types in Chapter 6). They might manage the employee profiles, which appear in multiple department sites, or manage company news articles, regardless of location. In fact, some editors might be better defined by what content types they are not allowed to create—some editors, for instance, might not be allowed to create advanced content like aggregations or image carousels.

- By editing interface

- Editors might be limited by the interface they’re allowed to use. In larger installations, it’s not uncommon to channel certain editors through specialized, custom-built interfaces designed to allow them to manage only the content under their control. For instance, if the receptionist at your company is responsible for updating the lunch menu on the intranet and nothing else, then he doesn’t need an understanding of the larger CMS interface and all the intricacies that go with it. Instead, it might be appropriate to build that person a special editing interface to manage the lunch menu and nothing else.

Several other specific editorial roles are common:

- Approvers

- This role is responsible for reviewing submitted content, ensuring it’s valid, accurate, and of acceptable quality, and then publishing that content. That is, approvers perform steps in one or more workflows. Many editors are also approvers, responsible for vetting content submitted by more junior editors. These editors may also have the right to approve their own content. Some approvers might have the ability to edit submitted content prior to publication (an editor-in-chief, for example), while other approvers might only have the ability to approve or reject (those in the legal or compliance department, for example). This role might only need to understand the content approval features of the CMS.

- Marketers

- This role is responsible for reviewing content for marketing impact, and managing the marketing value of the entire website. It requires an understanding of the marketing and analytics features of the CMS. For some sites, this is the dominant role because new content isn’t created nearly as often as existing content needs to be optimized, promoted, and analyzed.

- UGC/community managers

- This role is responsible for verifying the appropriateness of content submitted by users (user-generated content, or UGC), such as user profile information and blog comments. These managers are similar to approvers, but they only have control over UGC, rather than core editorial content (in some cases, this might be the majority of the content on the site). Additionally, given that the submission volume of UGC is often high, it’s commonly managed post-publication—inappropriate content is reviewed and removed after publication (or after a complaint is received), rather than holding it from publication until review. This role will only need to understand the CMS to the extent that allows them to moderate UGC. In some cases, the CMS provides separate tools for this, while in others this is handled as normal content.

- Translators

- This role is responsible for the translation of content from one language to another. Translators only need to understand the editorial functionality of the CMS to the extent required to add translations of specific content objects (perhaps even of only specific content attributes, in the event that content objects are only partially translated). We will talk about localization issues much more in Chapter 10.

Site planners are responsible for designing the website the CMS will manage. Several subroles exist:

- Content strategists

- This role is responsible for designing content, both holistically and tactically. As a byproduct of the content planning process, content strategists define the content types and interactions the website must support. This role will require knowledge of how the CMS models and aggregates content in order to understand any limitations on the design. Additional knowledge of the marketing features will be necessary if the content strategist is responsible for optimizing the marketing value of the site prior to launch.

- User experience (UX) designers and information architects

- These roles are responsible for organizing content and designing the users’ interaction with the website. They will need to understand how the CMS organizes content, and what facilities are available to aggregate and present content to end users.

- Visual designers

- This role is responsible for the final, high-fidelity design of the website (as opposed to lower-fidelity prototypes and user flows provided by previous roles). Visual designers don’t need intimate knowledge of the CMS, as CMS-related limitations will have guided the process up to their involvement. (In some cases, this role overlaps with template development, which we’ll discuss in the next section.)

Developers are responsible for installing, configuring, integrating, and templating the CMS to match the requirements of the project. Multiple categories of tasks that define different roles:

- CMS configuration

- This role is responsible for the installation and configuration of the CMS itself, including the establishment of the content model, creation of workflows and other editorial tools, creation of user groups, roles, and permissions, etc. This work is done at a fairly high level, through facilities and interfaces provided by the CMS.

- Backend (server) development

- This role is responsible for more low-level development performed in a traditional programming language (PHP, C#, Java, etc.) to accomplish more complex content management tasks, or to integrate the CMS with other systems. This developer should have experience in (1) the required programming language and (2) the API of the CMS.

- Frontend (client) development or templating

- This role is responsible for the creation of HTML, CSS, JavaScript, template logic, and other code required to present managed content in a browser. This developer needs only to know the templating language and architecture provided by the CMS, and how it integrates with HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. (Different template architectures and paradigms can vastly change the responsibilities of this role, as we’ll see in Chapter 9.)

Administrators are responsible for the continued operation of the CMS and the associated infrastructure. Within this group are several subroles:

- CMS administrator: This role is responsible for managing the CMS itself, which includes user and permission management, workflow creation and management, licensing management, and all other tasks not related to content creation.

- Server administrator: This role is responsible for the maintenance and support of the server(s) on which the CMS runs and/or deploys content. This is a traditional IT role, and the server administrator often has no understanding of the CMS itself other than the basic architecture required for it to run without error (operating system, runtime framework, web server, etc.). This role provides support when there’s an underlying server issue that prevents the CMS from functioning correctly.

- Database/storage administrator: This role is responsible for managing the database server and storage networks that hold the CMS content. This administrator needs very little understanding of the CMS, other than the file types, sizes, and aggregate volumes that will need to be stored and backed up.

The stakeholders of a CMS project are an amorphous group representing the people responsible for the results that the CMS is intended to bring about. Stakeholders are normally business or marketing staff (as opposed to editorial or IT staff) who look at the CMS simply as a means to an end.

In general, stakeholders are looking to a CMS to do one of two things:

- Increase revenue.

- Reduce costs and/or risk.

We’ll start by covering the Big Four of content management.

- Content modeling

- You need to describe the structure of content and store your content as a faithful representation of this structure.

- Content aggregation

- You need to logically organize content into groups and in relation to other content.

- Editorial workflow and usability

- You need to enable and assist the creation, editing, and management of content within defined boundaries.

- Publishing and output management

- You need to transform content in various ways for publication, and deliver the prepared content to publishing channels.

From there, we’ll review extended functionality:

- Multiple language handling

- Personalization, analytics, and marketing optimization

- Form building

- Content file management

- Image processing

- URL management

- Multisite management

- APIs and extensibility

- Plug-in architectures

- Reporting tools and dashboards

- Content search

- User and developer community support (yes, this is a feature too)

Every CMS has a content model. Even the simplest CMS has an internal, concrete representation of how it defines content.

Your content has been combined with presentational information—in this case, converted to HTML tags—and published to a specific location. Ideally, you could take those same words and use them to create a PDF, or, after publishing your web page, you could use the title of your press release and the URL to create a Facebook update.

These publication locations (email, web, Facebook, etc.) are often called channels. The media that is published to a channel might be referred to as a rendition or a presentation of content in a particular channel.

The relationship of content to published media is one to many: one piece of content can result in many presentations.

We can only do this if we separate our content and our presentation, which means modeling our core content as “purely” as possible.

Here’s a list of questions to ask with regard to a system’s content modeling features:

- What is the built-in or default content model? How closely does this match your requirements?

- To what extent can this model be customized?

- Does the system allow multiple types?

- Does the system allow content type inheritance? Does it allow multiple inheritance?

- Does the system allow for the datatyping of attributes?

- What datatypes are available to add attributes to types?

- What value, pattern, and custom validation methods are available?

- Can you add custom datatypes to the system based on your specific requirements?

- Does the system allow multiple values for attributes?

- What editorial interfaces are available for each datatype?

- Does the system allow an attribute to be a reference to another content object? Can the reference be to multiple objects? Can it be limited to only those objects of a certain type?

- What options are available for content embedding and page composition?

- Does the system allow for permissions based on types?

- Does the system allow for templating based on types?

- How close can this system get to the (usually unreachable) ideal of a custom relational database?

The shape of content refers to the general characteristics of a content model when taken in aggregate and when considered against the usage patterns of your content consumers.

- Serial

- This type of content is organized in a serial “line,” ordered by some parameter. An obvious example is a blog, which is a reverse-chronological aggregation of posts.

- Hierarchical

- This type of content is organized into a tree. There is a root content object in the tree that has multiple children, each of which may itself have one or more children, and so on. An example of this is the core pages of many simple informational websites. Websites are generally organized into trees—there is primary navigation (Products, About Us, Contact Us), which leads to secondary navigation (Product A, Product B, etc.).

- Tabular

- This type of content has a clearly defined structure of a single, dominant type, and is usually optimized for searching, not browsing. Imagine a large Excel spreadsheet with labeled header columns and thousands of rows. An example would be a company locations database. There might be 1,000 locations, all clearly organized into columns (address, city, state, phone number, hours, etc.).

- Network

- This type of content has no larger structure beyond the links between individual content objects. All content is equal, flat, and unordered in relation to other content, with nothing but links between the content to tie it together. An obvious example of this is a wiki.

- Relational

- This type of content has a tightly defined structural relationship between multiple highly structured content types, much like a typical relational database. The Internet Movie Database, for example, has Movies, which have one or more Actors, zero or more Sequels, zero or more Trivia Items, etc.

By making this aggregation a content object, we gain several inherent features of content:

- Permissions

- We could allow only certain editors to manage a particular Topic List.

- Workflow

- Changes to a Topic List might have to be approved.

- Versioning

- We might be able to capture and compare all changes to a particular Topic List.

- URL addressability

- This aggregation now has a URL from which it can be retrieved (more on this in the next section).

The content lifecycle can be described as having the following stages:

- Create

- Content is initiated in the CMS. It is not complete, but exists as a managed content object. It is not visible to the content consumer.

- Edit and Collaborate

- Content is actively edited and/or collaborated on by one or more editors. Content is still not visible.

- Submit and Approve

- Content is created and edited, and has been submitted for one or more approvals. Content is still not visible.

- Publish

- Content has been approved and is published on the website. Content in this state is visible to the content consumer.

- Archive

- Content is removed from public access, but not deleted. It is usually no longer visible.

- Delete

- Content is irreversibly deleted from the CMS.

These are tools that allow you to filter.

- By workflow or publication status

- By administrative task status

- By content owner

- By archival or deletion status

- By custom editorial metadata (for example, locating content tagged with “needs review”)

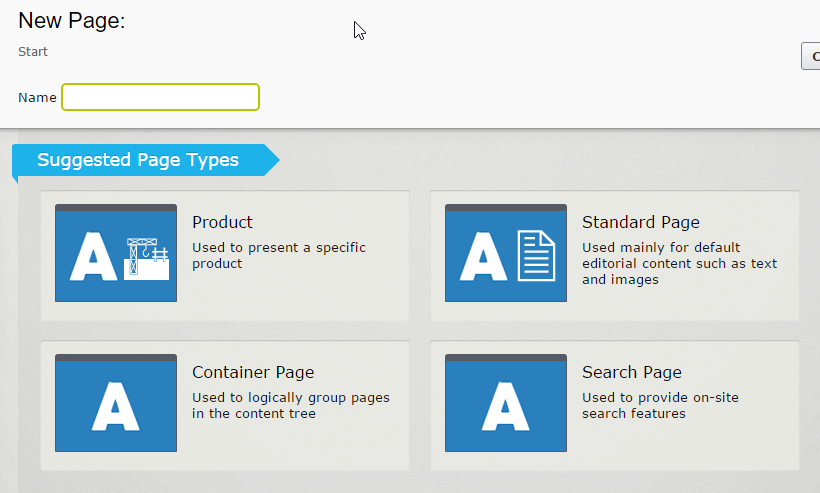

When creating a new content object, the first task of an editor is usually to select the content type on which to base it (see Chapter 6). The CMS needs to ensure the editor can select the appropriate content type for the situation, and not a content type that doesn’t work quite right, or will break the website should it be published.

Figure 8-1. The type selection interface in Episerver

There are two schools of thought about how content preview should relate to the editing interface:

- Presentation-free editing was the default standard for many years. In this case, the editor works in a standard web form, with text boxes, text areas, drop-down lists, etc. To preview content, the editor navigates to a separate interface, then back again to continue editing.

- In-context editing, by contrast, seeks to make the editing interface look as close to the final content production as possible. An editor might find himself editing in something that looks very much like the finished page, complete with styling. When he types the title, for instance, the letters come out in 24 pt Arial Bold, just like when the page will be published. The goal is to try to disguise that this is an editing interface at all, and make it seem like the editor is simply working in the finished page. Preview becomes effectively real-time.

Versioning is the act of not overwriting content with changes, but instead saving content in a new version of an existing content object.

Editors can use versioning in several ways:

- As a safeguard against improper or malicious changes. Versioning is like real-time backup for that single content object.

- As an audit trail to ensure they always have a record of what content was presented to the public at any given time, perhaps for legal and compliance reasons.

- To separate changes to content from the currently published content, so that changes can be approved and scheduled independently of the content currently shown to the public.

- To enable one version to be compared to another to determine what has changed, which is helpful for approvals (discussed later in this chapter).

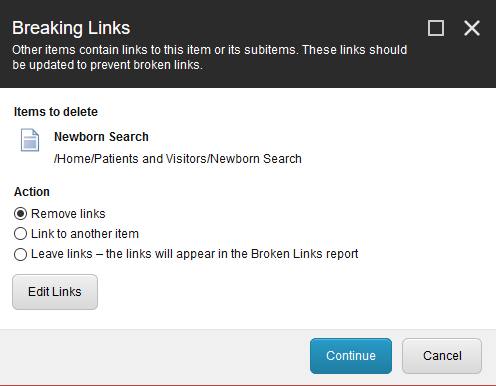

Two content objects can be related in a number of ways:

- The HTML of an attribute might contain a hyperlink to another content object.

- An attribute reference might link to another content object.

- A content object might be embedded in the rich text of another content object.

- The HTML of an attribute might contain embedded media that is a separate content object.

Some helpful functionality:

- A predeletion check can inform the editor that the content he’s about to delete is referenced from other content (see Figure 8-4).

- Broken link reports can identify content that links to a target that is no longer available, either due to forced deletion, content expiration, or permission changes.

- An orphaned content report could identify content not in use by any other content.

- Dependencies can be used to determine the cascading scope of changes. When content is published, for example, the system can know what other content needs to be republished, in the case of a decoupled CMS, or reindexed for search.

- Search optimization can use dependencies when weighting result pages, assuming that popular content is referenced more often and should be more heavily weighted. Other information architecture functionality might use the link graph to extract information from content relationships.

Figure 8-4. A deletion warning in Sitecore—the content pending deletion is depended on by other content, and the system needs to know how the editor wants to handle the broken dependencies

Publication scheduling has two basic forms:

- Scheduling of new content

- The ontent object isn’t displayed anywhere on the site until a point in time at which it appears.

- Scheduling of a new version

- The content object is displayed in its current form until a point in time, when a new version takes its place.

Oftentimes, editors are working on a content project that requires changes to multiple content objects separately. Editors would like these changes tracked as a group and scheduled, approved, and published together.

This is known by several names, but most commonly as a changeset (other common names are “project,” “edition,” and “package”). A changeset is created with all related content bound to it. The changeset itself is scheduled, rather than the individual content versions. When the changeset reaches publication, all of the content objects are published simultaneously.

At a given point in time, content is simply removed from publication. This means our imaginary arrow disappears from the stack completely, and no version of the content is considered to be published. This is not a deletion.

After an editor makes a change to content, he might be able to publish it directly, or he might have to submit the change for approval.

Two questions need to be resolved:

- Who gets notified?

- How are they notified?

Workflow is the movement of content through a map or network of discrete steps. A workflow step (sometimes called an “activity” or a “task”) is a clear boundary that defines a state the content is in at a moment in time.

Some common features include:

- The ability to create and assign a task, specifically bound to a content object or changeset. An editor might create a task entitled “Update the Privacy Policy,” then attach that content object to the task, and assign it to another editor. This often dovetails into workflow, as the act of creating the task might have created a workflow. Alternatively, a workflow might use the task subsystem heavily when notifying editors of pending approvals. In some cases, the tasks attached to a content object can be viewable in the administrative interface from that object.

- The ability to leave notes for other editors regarding specific content; provide notes on specific versions explaining what was changed; or have threaded, multiuser discussions about content.

- The ability to store editorial metadata (in the event that you want this data separate from the actual content model).

- The ability to have real-time group chats within the CMS interface.

In many systems, files are “second-class” content. You can manage them, but in a more rudimentary fashion than “first-class” content (modeled content types).

A permission—or, technically, an access control entry (ACE), an ACL is a bundle of ACEs—is an intersection between three things:

- User

- Action

- Object

The key here is to separate your content in its pure form—its raw, naked data—from the ways in which it’s used. Your article might consist of the following information (attributes, in the content model):

- Title

- Summary

- Image

- Byline

- Body

It might also need to have multiple attributes to help when it’s presented in various channels, such as:

- Tweet Body

- Sidebar Position

- Facebook Link Text

This information isn’t your content.

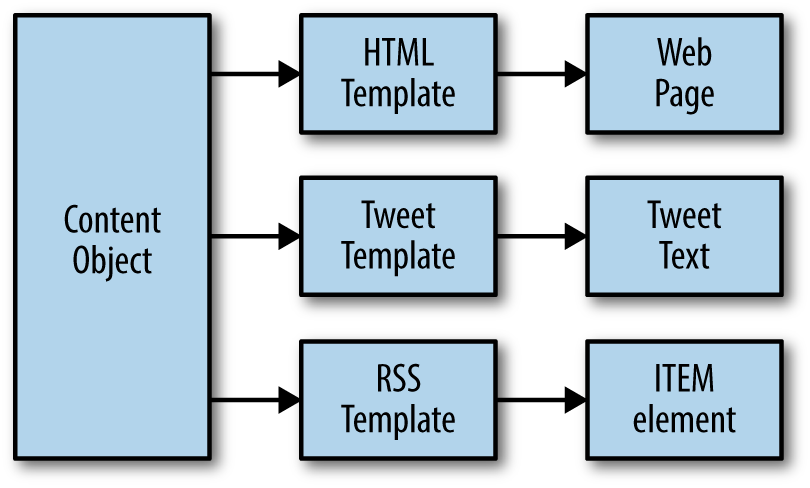

Templating is the process of generating output based on managed content. In a very general sense, the output will be a string of text characters, usually HTML.

A CMS blends two things together to generate output:

- Templating code, or text entered by a developer, usually created and stored in a file. Different templates create different output. One template might generate a web page, while another might generate a tweet (see Figure 9-1).

- Managed content, or text managed by an editor, created and stored in the CMS.

Figure 9-1. Multiple templates are provided to the same content object to provide multiple outputs

By “management,” I mean the system in which content is created, edited, and managed. By “delivery,” I mean the system from which content is consumed by a visitor.

In many cases, these are the same system. Editors manage content and visitors consume it from the same server, using the same execution environment. These systems are said to be “coupled.” Management and delivery are inextricably linked in the same environment.

Contrast this to a system where the authoring and management environment is on one server, and the delivery environment is on a completely different server, perhaps in a different data center, and even in a different geographic location entirely. Content is created and managed in one place, and is then transmitted to another place where it’s consumed by visitors. These systems are said to be “decoupled.” Management and delivery are separated into two environments.

When it comes to actually publishing content, the two options are handled quite differently:

- With a coupled system, the act of publishing content simply means changing a setting on the content to make it publicly available. From the first moment it’s created, content is already in the delivery environment; it’s just hidden from public view. Referring back to the versioning discussion in the last chapter, to make it available for public view, we simply mark one of the versions as “published.” It’s almost anticlimactic.

- With a decoupled system, we have to actually move the data from one environment to another. All content intended for publishing is gathered up from the management environment, then transmitted to another server entirely.

When discussing multilanguage content, some terms can be tricky. Here are a few definitions to keep in mind:

- Localization is the translation of content into another language.

- Internationalization is the development of software in such a way that it supports localization.

The language in which your visitor wants to consume content can be communicated via three common methods:

- The domain name from which the content is accessed

- A URL segment of the local path to the content

- The visitor’s browser preferences, communicated via HTTP header

- Anonymous Personalization

- A goal of any marketing-focused website is to adapt to each visitor individually.

- Analytics Integration

- Website analytics systems are not new, but there was a push some years ago to begin including this functionality inside the CMS.

- Marketing Automation and CRM Integration

- Beyond the immediate marketing role of the website, there’s a larger field of functionality called “marketing automation” that seeks to unify the marketing efforts of an organization through multiple channels.

- Clearly, your actions are being tracked across multiple platforms, with all your actions feeding a centralized profile based on you in the vendor’s customer relationship management (CRM) system.

- This was in opposition to “friendly” or “pretty” URLs:

/articles/two_column_layout.asp?article_id=354 - Some semantic value to the content:

/articles/2015/05/politics/currency-crisis-in-china

A lot of reporting is simply ad hoc. The ultimate level of functionality in this space would be for an editor to simply ask a plain-language question of the content repository, Siri-style: “Repository, show me all of the articles in the politics section that have a status of Draft."

In these cases, a competent API (as discussed in the previous section) coupled with a solid reporting framework is the best solution. Developers who have good searching tools and a framework to quickly build and deploy reports can hopefully respond quickly to editors’ needs for developing reports when required.

Requested features of content searching can include any of the following:

- Full-text indexing

- Return results for nonadjacent terms (for example, content that includes the phrase “fishing in the lake” will match when someone searches for “lake fishing”).

- Spellchecking and fuzzy query matching

- Understand search terms that almost match and account for them.

- Stemming

- Conjugate verbs and normalize suffixes (for example, a search for “swimming” also returns results for “swim” and “swam”).

- Geo-searching

- Search for locations based on geographic coordinates—either distance from a point, or locations contained within a “bounding box.”

- Phonetic or Soundex matching

- Calculate how a word might sound and search for terms that sound the same.

- Repository isolation

- Search only a specific section of the content geography.

- Synonyms and authority files

- Specify that two terms are similar and should be evaluated identically.

- Boolean operators

- Allow users to add AND, OR, and NOT logic to their queries.

- Biasing

- Influence search results by increasing the score for content related to a specific search term, and perhaps allow editors or administrators to change bias settings from the interface.

- Result segregation

- Allow for the visual separation of specific content at the top of the results.

- Related content searching

- Suggest content related to the content a user is searching for (“show me more like this”).

- Type-ahead or predictive searching

- Attempt to complete a user’s search term in the search box while the user types.

- Faceting or filtering

- Let users refine their searches to specific parameter values (this represents a mixing of parametric and content search paradigms).

- Search analytics and reporting

- Track search terms, result counts, and clickthrough on result pages.

- Stopwords

- Remove common words from indexed content.