-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 58

Original research

While most of cpp-sort's algorithms are actually taken from other open-source projects, and/or naive implementations of well-known sorting algorithms, it also contains a bit of original research. Most of the things described here are far from being ground-breaking discoveries, but even slight improvements to known algorithms deserve to at least be documented so that they can be reused, so... here we go.

You can find some experiments and interesting pieces of code in my Gist too - generally related to this library -, even though it doesn't always come with proper explanation or build instructions.

One of the main observations which naturally occured as long as I was putting together this library was about the best time & space complexity tradeoffs depending on the iterator categories of the different sorting algorithms (only taking comparison sorts into account):

- Algorithms that work on random-access iterators can run in O(n log n) and O(1) space, and can even be stable with such guarantees (block sorts being the best examples).

- Unstable algorithms that work on forward or bidirectional iterators can run in O(n log n) time and O(1) space: QuickMergesort can be implemented with a bottom-up mergesort and a raw median-of-medians algorithm (instead of the introselect mutual recursion), leading to such complexity.

- Stable algorithms that work on forward or bidirectional iterators can run in O(n log n) time and O(n) space (mergesort), or in O(n log² n) time and O(1) space (ex: mergesort with in-place merge).

- Taking advantage of the list data structure allows for comparison sorts running in O(n log n) time and O(1) space, be it for stable sorting (mergesort) or unstable sorting (melsort), but those techniques can't be generically retrofitted to generically work with bidirectional iterators

Now, those observations/claims are there to be challenged: if you know a stable comparison sort that runs on bidirectional iterators in O(n log n) time and O(1) space, don't hesitate to be the challenger :)

The vergesort is a new sorting algorithm which combines merge operations on almost sorted data, and falls back to another sorting algorithm when the data is not sorted enough. Somehow it can be considered as a cheap preprocessing step to take advantage of almost-sorted data when possible. Just like TimSort, it achieves linear time on some patterns, generally for almost sorted data, and should never be worse than O(n log n log log n) in the worst case - though no in-depth formal analysis has been performed.

Best Average Worst Memory Stable

n n log n n log n log log n n No

n n log n n log n log n No

The two variations in space and time complexity depend on whether enough memory is available for the merging operation to work in O(n) time, or whether it falls back on another algorithm that works in O(n log n) time and O(1) space.

While vergesort has been designed to work with random-access iterators, there also exists a version that works with bidirectional iterators. The algorithm is slightly different and a bit slower because it can't as easily jump through the collection. The complexity of that bidirectional iterators algorithm can get down to the same time as the random-access one when quick_merge_sort is used as the fallback algorithm.

The actual complexity of the algorithm is O(n log n log log n), but interestingly it is only reached in one of its paths that is among the fastest in practice. It is also possible to make vergesort stable but tweaking its reverse runs detection algorithm and making it fallback to a stable sorting algorithm.

This sorting algorithm also exists as a standalone repository.

The double insertion sort is a somewhat novel sorting algorithm to which I gave what is probably the worst name ever, but another name couldn't describe better what the algorithm does (honestly, I would be surprised if it hadn't been discovered before, but I couldn't find any information about it anywhere). The algorithm is rather simple: it sorts everything but the first and last elements of a collection, switches the first and last elements if they are not ordered, then it inserts the first element into the sorted sequence from the front and inserts the last element from the back.

As the regular insertion sort, it comes into two flavours: the version that uses a liner search to insert the elements and the one that uses a binary search instead. While the binary search version offers no advatange compared to a regular binary insertion sort, the linear version has one adavantage compared to the basic linear insertion sort: even in the worst case, it shouldn't take more than n comparisons to insert both values into the sorted sequence, where n is the size of the collection to sort, making less comparisons and less moves than a regular linear insertion sort on average.

Best Average Worst Memory Stable Iterators

n n² n² 1 No Bidirectional

A double liner gnome sort (same as double linear insertion sort, but putting the value in place thanks to a series of swaps) was originally used in cpp-sort to generate small array sorts, but it has since been mostly dropped in favour of better alternatives depending on the aim of the small array sort.

A half-cleaner network is a comparison network of depth 1 in which input every line i is compared with line i + n/2 for i = 1, 2, ..., n/2. For the sake of simplicity, we only consider networks whose size is even. This kind of network is mostly mentioned when describing a particular step in bitonic sorting networks. I played a bit with half-cleaners to try to create new merging networks. The results are of course not as good as the existing sorting networks, but interesting nonetheless.

When given two sorted inputs of size n/2, a half-cleaner seems to have the following property: the first element of the output will be the smallest of the network and the last element of the output will be the greatest of the network. Moreover, both halves of the output are sorted. That means that it is possible to create what I would call a shrinking merge network that half-cleans the input of size n, then half-cleans the output of size n-2, then half-cleans the output of size n-4, etc... While easy to implement, it gives a merging network with (n/4)*(n/4+1) compare-exchanges and a depth of n/2, which is rather bad...

Anyway, the nice property of this half-cleaning is that it can be performed on networks of any size (as long as the size is even). It means that it is for example possible to half-clean an input of size 12 (elements 1 and 12 will be in their final position, elements [2-6] and [7-11] are sorted), then to sort the elements 2 and 11, and to perform an odd-even merge on the elements [3-10]. Once again, it does not produce better results than an odd-even merge, but it's easy to implement for any size of arrays and is sometimes as good as an odd-even merge.

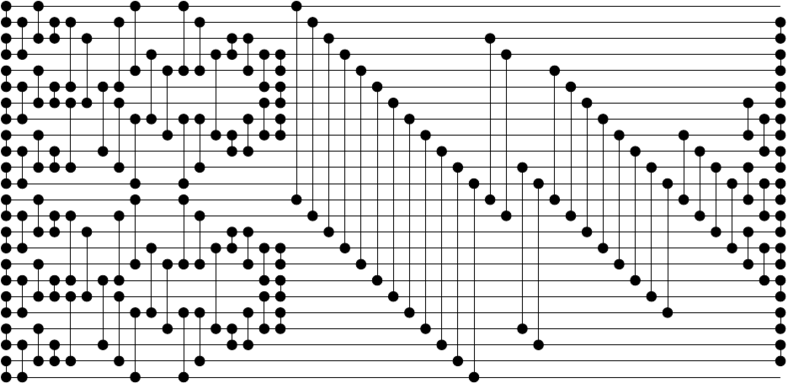

The following 24 inputs network uses the technique described in the previous section:

- Sort the first two halves with the best 12-sorter known so far

- Use half-cleaner to initiate a partial merge of the two arrays

- Compare-exchange elements 2-12, 3-13, 10-20 and 11-21

- Perform an odd-even merge on elements 4-19

- Compare-exchange elements 1-2, 3-4, 19-20 and 21-22

The resulting network has 123 compare-exchanges and a depth of 18. The 12-12 merging network has 45 compare-exchanges, which is equivalent to a 12-12 odd-even merge.

[[0, 1],[2, 3],[4, 5],[6, 7],[8, 9],[10, 11],[12, 13],[14, 15],[16, 17],[18, 19],[20, 21],[22, 23]]

[[1, 3],[5, 7],[9, 11],[0, 2],[4, 6],[8, 10],[13, 15],[17, 19],[21, 23],[12, 14],[16, 18],[20, 22]]

[[1, 2],[5, 6],[9, 10],[13, 14],[17, 18],[21, 22]]

[[1, 5],[6, 10],[13, 17],[18, 22]]

[[5, 9],[2, 6],[17, 21],[14, 18]]

[[1, 5],[6, 10],[0, 4],[7, 11],[13, 17],[18, 22],[12, 16],[19, 23]]

[[3, 7],[4, 8],[15, 19],[16, 20]]

[[0, 4],[7, 11],[12, 16],[19, 23]]

[[1, 4],[7, 10],[3, 8],[13, 16],[19, 22],[15, 20]]

[[2, 3],[8, 9],[14, 15],[20, 21]]

[[2, 4],[7, 9],[3, 5],[6, 8],[14, 16],[19, 21],[15, 17],[18, 20]]

[[3, 4],[5, 6],[7, 8],[15, 16],[17, 18],[19, 20]]

[[0, 12],[1, 13],[2, 14],[3, 15],[4, 16],[5, 17],[6, 18],[7, 19],[8, 20],[9, 21],[10, 22],[11, 23]]

[[2, 12],[3, 13],[10, 20],[11, 21]]

[[4, 12],[5, 13],[6, 14],[7, 15],[8, 16],[9, 17],[10, 18],[11, 19]]

[[8, 12],[9, 13],[10, 14],[11, 15]]

[[6, 8],[10, 12],[14, 16],[7, 9],[11, 13],[15, 17]]

[[1, 2],[3, 4],[5, 6],[7, 8],[9, 10],[11, 12],[13, 14],[15, 16],[17, 18],[19, 20],[21, 22]]

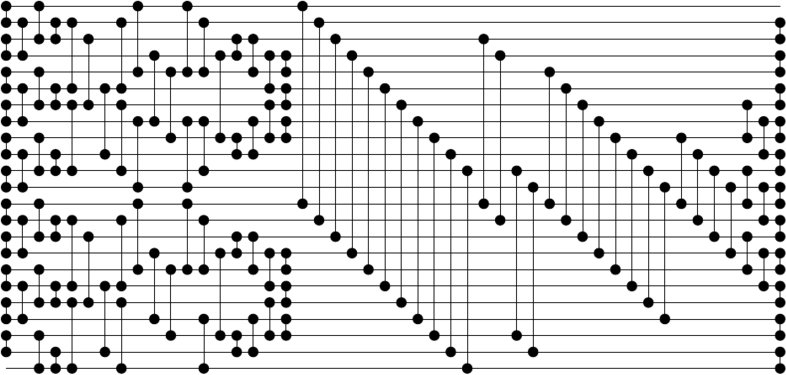

Removing the first or the last line of the network yields the following 23-sorter with 118 compare-exchanges and a depth of 18.

[[0, 1],[2, 3],[4, 5],[6, 7],[8, 9],[10, 11],[12, 13],[14, 15],[16, 17],[18, 19],[20, 21]]

[[1, 3],[5, 7],[9, 11],[0, 2],[4, 6],[8, 10],[13, 15],[17, 19],[12, 14],[16, 18],[20, 22]]

[[1, 2],[5, 6],[9, 10],[13, 14],[17, 18],[21, 22]]

[[1, 5],[6, 10],[13, 17],[18, 22]]

[[5, 9],[2, 6],[17, 21],[14, 18]]

[[1, 5],[6, 10],[0, 4],[7, 11],[13, 17],[18, 22],[12, 16]]

[[3, 7],[4, 8],[15, 19],[16, 20]]

[[0, 4],[7, 11],[12, 16]]

[[1, 4],[7, 10],[3, 8],[13, 16],[19, 22],[15, 20]]

[[2, 3],[8, 9],[14, 15],[20, 21]]

[[2, 4],[7, 9],[3, 5],[6, 8],[14, 16],[19, 21],[15, 17],[18, 20]]

[[3, 4],[5, 6],[7, 8],[15, 16],[17, 18],[19, 20]]

[[0, 12],[1, 13],[2, 14],[3, 15],[4, 16],[5, 17],[6, 18],[7, 19],[8, 20],[9, 21],[10, 22]]

[[2, 12],[3, 13],[10, 20],[11, 21]]

[[4, 12],[5, 13],[6, 14],[7, 15],[8, 16],[9, 17],[10, 18],[11, 19]]

[[8, 12],[9, 13],[10, 14],[11, 15]]

[[6, 8],[10, 12],[14, 16],[7, 9],[11, 13],[15, 17]]

[[1, 2],[3, 4],[5, 6],[7, 8],[9, 10],[11, 12],[13, 14],[15, 16],[17, 18],[19, 20],[21, 22]]

When I originally released them, those networks were the smallest 23-sorters and 24-sorters (though other networks witht the same number of comparators existed). Nowadays there are way better networks for 23 and 24 inputs.

I tried to apply the same technique to create a 40-sorter, but the resulting 20-20 merging network has 93 compare-exchanges while the 20-20 odd-even merge network has 89. This merging technique probably becomes gradually worse compared to odd-even merge.

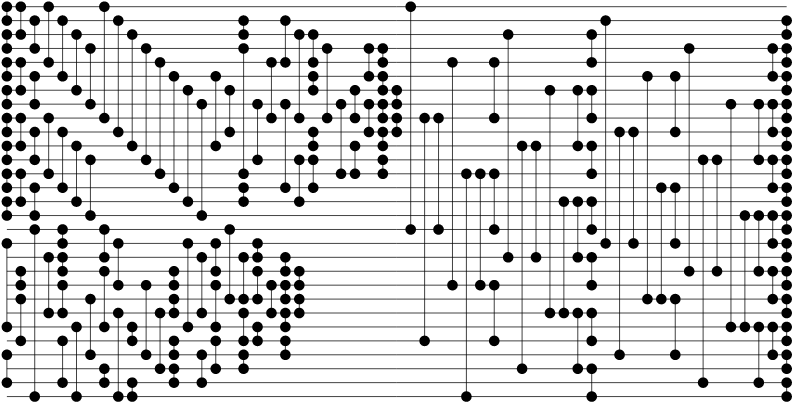

Note: the following has since been improved upon: SorterHunter found a network that sorts 29 inputs with 164 compare-exchange operations.

The following sorting network for 29 inputs has 165 compare-exchange operations (CEs), which is one less that the most size-optimal 29-input sorting networks that I could find in the literature. Here is how I generated it: first it sorts the first 16 inputs and the last 13 inputs independently. Then it merges the two sorted subarrays using a size 32 Batcher odd-even merge network (the version that does not need the inputs to be interleaved), where all compare-exchange operations working on indexes greater than 28 have been dropped. Dropping comparators in such a way is ok: consider that the values at the indexes [29, 32) are greater than every other value in the array to sort, and it will become intuitive that dropping them generates a correct merging network of a smaller size.

That said, even though I have been unable to find a 29-input sorting network with as few compare-exchange operations as 165 in the literature, I can't claim that I found the technique used to generate it: the 1971 paper A Generalization of the Divide-Sort-Merge Strategy for Sorting Networks by David C. Van Voorhis already describes the as follows:

The improved 26-,27-,28-, and 34-sorters all use two initial sort units, one of them the particularly efficient 16-sorter designed by M. W. Green, followed by Batcher's [2,2] merge network.

The paper does not mention a better result than 166 CEs for the 29-input sorting networks, but that's only because our solution relies on a 13-input sorting networks that uses 45 CEs, while the best known such network in 1971 used 46 CEs. I couldn't find any resource using the technique to improve the 29-input sorting network since then, even though some of them mention a 156-CE 28-input sorting network that has apparently only been described in the aforementioned paper.

[[0, 1],[2, 3],[4, 5],[6, 7],[8, 9],[10, 11],[12, 13],[14, 15],[17, 23],[25, 27]]

[[0, 2],[4, 6],[8, 10],[12, 14],[19, 20],[21, 24]]

[[1, 3],[5, 7],[9, 11],[13, 15],[16, 28]]

[[0, 4],[8, 12],[18, 22]]

[[1, 5],[9, 13],[16, 17],[18, 19],[20, 22],[24, 27]]

[[2, 6],[10, 14],[23, 28]]

[[3, 7],[11, 15],[21, 25]]

[[0, 8],[16, 18],[19, 23],[26, 27]]

[[1, 9],[17, 20],[22, 28]]

[[2, 10],[23, 24],[27, 28]]

[[3, 11],[20, 25]]

[[4, 12],[22, 26]]

[[5, 13],[19, 20],[21, 22],[24, 25],[26, 27]]

[[6, 14],[17, 23]]

[[7, 15],[18, 22],[25, 27]]

[[5, 10],[17, 19],[20, 23],[24, 26]]

[[6, 9],[16, 21]]

[[3, 12],[13, 14],[1, 2],[18, 21],[22, 24],[25, 26]]

[[7, 11],[17, 18],[19, 21],[23, 24]]

[[4, 8],[20, 22]]

[[1, 4],[7, 13],[18, 19],[20, 21],[22, 23],[24, 25]]

[[2, 8],[11, 14],[19, 20],[21, 22]]

[[2, 4],[5, 6],[9, 10],[11, 13]]

[[3, 8]]

[[7, 12]]

[[6, 8],[10, 12]]

[[3, 5],[7, 9]]

[[3, 4],[5, 6],[7, 8],[9, 10],[11, 12]]

[[6, 7],[8, 9]]

[[0, 16]]

[[8, 24]]

[[8, 16]]

[[4, 20]]

[[12, 28]]

[[12, 20]]

[[4, 8],[12, 16],[20, 24]]

[[2, 18]]

[[10, 26]]

[[10, 18]]

[[6, 22]]

[[14, 22]]

[[6, 10],[14, 18],[22, 26]]

[[2, 4],[6, 8],[10, 12],[14, 16],[18, 20],[22, 24],[26, 28]]

[[1, 17]]

[[9, 25]]

[[9, 17]]

[[5, 21]]

[[13, 21]]

[[5, 9],[13, 17],[21, 25]]

[[3, 19]]

[[11, 27]]

[[11, 19]]

[[7, 23]]

[[15, 23]]

[[7, 11],[15, 19],[23, 27]]

[[3, 5],[7, 9],[11, 13],[15, 17],[19, 21],[23, 25]]

[[1, 2],[3, 4],[5, 6],[7, 8],[9, 10],[11, 12],[13, 14],[15, 16],[17, 18],[19, 20],[21, 22],[23, 24],[25, 26],[27, 28]]

The mountain sort is a new indirect sorting algorithm designed to perform a minimal number of move operations on the elements of the collection to sort. It derives from cycle sort and Exact-Sort but is still slightly different: the goal of cycle sort is to perform a minimal number of writes to the original array, and while Exact-Sort indeed performs the same number of moves and writes to the original array than cycle sort, the description says that it's the best algorithm to sort fridges by price, so its goal would actually be closer to that of mountain sort. However, both have a rather similar implementation: find cycles of values to rotate, swap the first value into a temporary variable, find where it goes, swap the contents of the temporary variable with the value in the location, find where the new value goes, etc... Exact-Sort is a bit more optimized but the lookup still makes it a O(n²) algorithm. Mountain sort chooses to consume more memory and to store the iterators and to sort them beforehand so that the move part can be done with only one write to a temporary variable per cycle. I don't think that any sorting algorithm can perform less moves than mountain sort. Its basic implementation relies on std::sort to sort the iterators, more or less leading to the following complexity:

Best Average Worst Memory Stable

n log n n log n n log n n No

However, cpp-sort implements it as a sorter adapter so you can actually choose the sorting algorithm that will be used to sort the iterators, making it possible to use a stable sorting algorithm instead. Note that the memory footprint of the algorithm is negligible when the size of the elements to sort is big since only iterators and booleans are stored. It makes mountain sort the ideal sorting algorithm when the objects to sort are huge and the comparisons are cheap (remember: you may want to sort fridges by price, or mountains by height). You can find a standalone implementation of mountain sort in the dedicated repository.

cpp-sort ships an implementation of a poplar sort which roughly follows the algorithm as described by Coenraad Bron and Wim H. Hesselink in their paper Smoothsort revisited. However, I later managed to improve the space complexity of the algorithm by making the underlying poplar heap data structure a proper implicit data structure. You can read more about this experiment in the dedicated project page. The algorithm used by poplar_heap does not used the O(1) space complexity algorithm because it was measured to be slower on average that the old algorithm with O(log n) space complexity.

I later realized that the data structure I called poplar heap had already been described by Nicholas J. A. Harvey and Kevin Zatloukal under the name post-order heap. I however believe that some of the heap construction methods described in my repository are novel.

I borrowed some ideas from Edelkamp and Weiß QuickXsort and QuickMergesort algorithms, and came up with a version of QuickMergesort that uses a median-of-median selection algorithm to split the collection into two partitions respectively two thirds and one thirds of the original one. This allows to use an internal mergesort on the left partition while maximizing the number of elements merged in one pass. Then the algorithm is recursively called on the smaller partition, leading to an algorithm that can run in O(n log n) time and O(1) space on bidirectional iterators.

Somehow Edelkamp and Weiß eventually published a paper afew years later decribing the same flavour of QuickMergesort with properly computed algorithmic complexities. I have a standalone implementation of quick_merge_sort in another repository, albeit currently lacking a proper explanation of how it works. It has the time and space complexity mentioned earlier, as opposed to the cpp-sort version of the algorithm where I chose to have theoretically worse algorithms from a complexity point of view, but that are nonetheless generally faster in practice.

The measure of presortedness Mono is described in Sort Race by H. Zhang, B. Meng and Y. Liang. They describe it as follows:

Intuitively, if Mono(X) = k, then X is the concatenation of k monotonic lists (either sorted or reversely sorted).

It computes the number of ascending or descending runs in X. Technically the definition in the paper makes it return 1 when the X is sorted, which goes against the original definition of a measure of presortedness by Mannila, which starts with the following condition:

If X is sorted, then M(X) = 0

Therefore we redefine Mono(X) as the number of non-increasing and non-decreasing consecutive runs of adjacent elements that need to be removed from X to make it sorted.

- Mono ⊇ Runs: this relation is already mentioned in Sort Race and rather intuitive: since Mono detects both non-increasing and non-decreasing runs, it is as least as good as Runs that only detects non-decreasing runs.

- SMS ⊇ Mono: this one seems intuitive too: SMS which removes runs of non-adjacent elements should be at least as good as Mono which only removes runs of adjacent elements.

- Enc ⊇ Mono: when making encroaching lists, Enc is guaranteed to create no more than one such new list per non-increasing or non-decreasing run found in X, so the result will be at most as big as that of Mono. However Enc can also find presortedness in patterns such as {5, 6, 4, 7, 3, 8, 2, 9, 1, 10} where Mono will find maximum disorder. Therefore Enc(X) should always be at most as big as Mono(X).

The following relations can be transitively deduced from the results presented in A framework for adaptive sorting:

- Mono ⊋ Exc: we know that SMS ⊇ Mono and SMS ⊋ Exc

- Mono ⊋ Inv: we know that SMS ⊇ Mono and SMS ⊋ Inv

- Hist ⊋ Mono: we know that Mono ⊇ Runs and Hist ⊋ Runs

The following relations have yet to be analyzed:

- Mono ⊇ Max

- Mono ≡ SUS

- Osc ⊇ Mono

- Home

- Quickstart

- Sorting library

- Comparators and projections

- Miscellaneous utilities

- Tutorials

- Tooling

- Benchmarks

- Changelog

- Original research