Learning Clojure by writing a Clojure parser. In Clojure.

So you want to learn Clojure? Parse it. In Clojure. Oh and do it with Monads. At least that's how we do things in GeekSkool.

GeekSkool is an intensive 3-month programme where programmers come to improve their skills. The preferred way that Santosh Rajan, the founder of GeekSkool, likes to do this is by throwing daunting challenges at the unsuspecting student.

So we're going to learn Clojure by 'parsing' Clojure, using Clojure. But what exactly do we mean by 'parsing'?

In this project, parsing means converting valid Clojure code into something called an Abstract Syntax Tree, or AST for short.

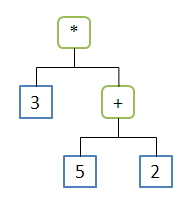

Any piece of code can be represented as a tree of objects and operators and functions. Here is some simple Clojure code and the tree that represents it:

(* 3 (+ 5 2))Now we can hardly expect the parser to spit out an image like this - what we want is a data structure that represents this tree. In Clojure, that would be a map - of parents and children. Maps in Clojure look like this:

{key value}

{parent [child1 child2 ...]}If we look at the tree again, we see that:

+ has two children: 5 and 2

* has two children: 3, and + with two children 5 and 2

This implies + could be mapped to a vector containing 5 and 2 (vector because there is an implicit order to the children, and also the Clojure convention is to put arguments in vectors):

{+ [5 2]}* can then be mapped to a vector containing 3 and the afore-mentioned map:

{* [3 {+ [5 2]}]}So

is

{* [3 {+ [5 2]}]}OK. So we are going to write a Clojure program that takes simple Clojure code as an input, and returns a map like the one above as the output, except with more helpful annotations.

We'll start by breaking up the problem into small, solvable pieces. We are only going to parse a subset of Clojure, with the following language objects:

- Numbers

- Strings

- Symbols (Literals which generally name other objects)

- Keywords (Symbols prefaced by ':' used especially in maps)

- Identifiers (Symbols which are the names of functions defined in the program, and built-in functions)

- Booleans (The symbols true and false)

- Back-ticks, Tildes and Ampersands (so we can implement simple macros)

- Parentheses

- Square brackets

- Operators

- Vectors ([arg1 arg2..] We will ignore other types of collections for now)

These objects and characters composed together, form S-expressions in the following format:

(func-name arg1 arg2 arg3...)(Optionally, macro body expressions can start with back-ticks before the opening parens - but we'll get to that later)

Function names can only be composed by the following in our subset of Clojure:

- Operators

- Keywords (when applied to maps, for example)

- Identifiers

Arguments can be composed by any of the following:

- Numbers

- Strings

- Symbols

- Keywords

- Booleans

- Vectors

- Tildes (Prefaced to dereferencable symbols in the Macro-body - more later...)

- Function names (functions can be passed as arguments)

- S-expressions themselves (nested expression as in our example above)

We will obviously have to parse the parentheses as well to understand where an expression begins, and where it ends.

So let's start by just parsing these individual components and then move on to composing these parsers together to parse function names and arguments - using the Parser Monad.

What exactly does a parser look like?

A parser is a function that takes, say, a string as an input and returns two things:

- A 'consumed' part

- The rest of the string

or

- nil

if it doesn't find what it's looking for.

Parser :: String -> [Anything, String] | nilSo a space parser could take

" the rest of the string"

and return

[" ", "the rest of the string"]

"string without starting space" would just return nil.

This is what it looks like in poorly written, non-idiomatic Clojure:

(defn parse-space [code]

(let [space (re-find #"^\s+" code)]

(if (nil? space)

nil

[space (extract space code)])))'Extract' here is a helper function that does exactly what it says on the tin.

Similarly,

(defn parse-newline [code]

(if (= \newline (first code))

[\newline (apply str (rest code))]

nil))

(defn parse-number [code]

(let [number (re-find #"^[+-]?\d+[.]?[\d+]?" code)]

(if (nil? number)

nil

[(read-string number) (extract number code)])))

(defn parse-string [code]

(let [string (last (re-find #"^\"([^\"]*)\"" code))]

(if (nil? string)

nil

[string (apply str (drop (+ 2 (count string)) code))])))

(defn parse-square-bracket [code]

(let [char (first code)]

(if (= \[ char)

[char (extract char code)]

nil)))

(defn parse-close-square-bracket [code]

(let [char (first code)]

(if (= \] char)

[char (extract char code)]

nil)))

(defn parse-round-bracket [code]

(let [char (first code)]

(if (= \( char)

[char (extract char code)]

nil)))

(defn parse-close-round-bracket [code]

(let [char (first code)]

(if (= \) char)

[char (extract char code)]

nil)))So a whole host of simple parsers like this can be given the responsibility of parsing little pieces of the code such as numbers, strings, symbols and identifiers.

We are going to combine little parsers like these to parse more complex structures - and this is where things get interesting.

Cue Monads.

Combining or composing functions is something we are very familiar with when it comes to, say, math.

We can easily chain a series of mathematical functions such as these without worrying if the whole, rube-goldberg structure will work or not.

In Clojure (with mythical 'sqrt' & 'sqr' functions), this would look like:

(/ (+ (- (+ x 1) (sqrt (sqr (- x 1)))) (sqrt (- (+ x 1) (sqrt (sqr (- x 1)))))) 4)No big deal.

This is because all these functions have similar signatures:

Math-function1 :: Number -> Number --takes a Number as input, returns a number as output

Math-function2 :: Number -> Number -> Number --takes two numbers as input, returns a number as outputWe immediately see that any function that takes two numbers and returns a number can easily be composed with another function and number. This combination will return a number, which can again be composed with yet another function which only takes one number as a parameter.

(Math-func1 (Math-func2 (Math-func2 n1 n2) n3))

We just have to be careful that the right number of parameters are passed to the corresponding function. This is easy enough to do with straight-forward syntax. Math-func1 always takes one parameter, and Math-func2 takes two. The + function takes two numbers, but the 'sqr' function takes only one.

But what about functions that have dissimilar signatures?

Func1 :: String -> String --takes a String, returns a String

Func2 :: String -> Number --takes a String, returns a Number

Func3 :: String -> Boolean --takes a String, returns a BooleanCan we compose such functions with the same ease with which we compose math functions?

We would like to do something like this (switching to parenthesised parameter syntax here):

Func1(parameter1) -> result1

Func2(result1) -> result2

Func3(result2) -> result3Or,

Func3(Func2(Func1(parameter1)))It's clear this won't work because Func3 expects a String, but Func2 returns a Number(of some kind).

What if we modified our functions to do something a little odd - they return their values, only in some kind of box (which could be an array, or list or anything, really):

Func1 :: String -> Box[String] --The return type is Box, we are showing the contents for clarity

Func2 :: String -> Box[Number]

Func3 :: String -> Box[Boolean]Now all we need to do is modify the parameters to be boxes as well:

Func1 :: Box[String] -> Box[String] --takes a Box, returns a Box

Func2 :: Box[String] -> Box[Number] --takes a Box, returns a Box

Func3 :: Box[String] -> Box[Boolean] --takes a Box, returns a BoxThis almost works - we can legally pass the result of one function to another since each expects a box and spits out a box. But then Func3 which expects to find a string in the box ends up getting a box with a number. Each of our functions need strings in their boxes to work.

Ok, so what if:

Func1 :: Box[Anything, String] -> Box[String, String]

Func2 :: Box[Anything, String] -> Box[Number, String]

Func3 :: Box[Anything, String] -> Box[Boolean, String]Now our functions can be combined willy-nilly just like mathematical functions!

But wait a minute - this is crazy! Why distort and boxify my nice, straight-forward functions just because of this threading business? Why??

Well, because, unlike imperative programs, a purely functional program is just that - a series of functions that are threaded into each other - one passing results to the next until the output of the program just pops out. And we all know that purely functional programs are the bees knees. That's why.

In fact, apart from the simple, easy building-block functions that perform a well-defined and small part of the program's task, most of the (spaghetti) code we write are complicated functions whose only job is to take the result of one function and transform it appropriately for input into the next function. This code handles the flow of the program, and tends to be hard to grok and painful to maintain, as their internal logic is almost entirely dependent on the functions they connect together. We all know what happens when the internals of one function are very dependent on that of another - changes to one part spread with epidemic proportions and speed across the entire pogram.

Wouldn't it be wonderful if we could abstract this glue code into a general form that allows us to thread functions with different signatures according to some general patterns? Then our code could just be composed of simple worker functions and a generic threading framework.

Well, that's exactly what Monads do.

But first, let's (almost) restore your simple, straight-forward functions to their (almost) non-boxy form and see if we can make things work in another, more clever way.

Let's step back from here:

Func1 :: Box[Anything, String] -> Box[String, String] --takes a Box, returns a Box

Func2 :: Box[Anything, String] -> Box[Number, String] --takes a Box, returns a Box

Func3 :: Box[Anything, String] -> Box[Boolean, String] --takes a Box, returns a BoxTo here:

Func1 :: String -> Box[String, String] --takes a String, returns a Box

Func2 :: String -> Box[Number, String] --takes a String, returns a Box

Func3 :: String -> Box[Boolean, String] --takes a String, returns a Box(Look familiar? This is like our parser, but not quite)

Now let's just replace box with M (for Monadic Value), and String, Number, Boolean with a, b & c to be more general.

Func1 :: a -> Ma --takes an a, returns a Monadic a (for now, think of this as 'Boxed' a)

Func2 :: a -> Mb --takes an a, returns a Monadic b

Func3 :: b -> Mc --takes a b, returns a Monadic cSo the only change to our functions is that they take 'regular' values and return Monadic values.

Now, instead of just passing the result of one function to the next, lets create something called a Monadic Bind to thread the functions together.

Now this is a little involved, so let's pay attention:

M-bind :: M-value -> (fn :: value -> M-value) -> M-value --take a Monadic value & a Monadic function, return a --Monadic valueSo M-bind is a function that takes two parameters:

M-value, a Monadic value.(fn :: value -> M-value), A function which takes a value and returns a Monadic value

And it returns:

M-value, a Monadic value.

Let's write this out using Func1 & Func2 and we'll see why this is brilliant.

But first, in Haskell (the motherlode of Monads), M-bind looks like this: >>= - let's use this representation, just to seem a bit more intelligent.

>>= :: M a -> (fn :: a -> M b) -> M bSo to M-bind two of our function together, we >>= them like so:

Func1(a) >>= Func2Func1 returns M a, so this expands to:

Func1 :: a -> M a >>= Func2

Func1 :: a -> M a >>= Func2 :: a -> M b

M a >>= Func2 :: a -> M b>>= is an infix operator, so the two expressions on each side of the operator are taken as parameters:

>>= :: M a -> Func2 -> M b

>>= M a -> Func2 :: a -> Mb