Tree-Buf is a data-oriented, data-driven serializer built for real-world data.

- Better than GZip compression, faster than other uncompressed formats

- Self-describing files that can be read with no schema

- Flexible format supports Rust style enums and more

This test compares the serialization of a complex GraphQL response containing 1000 entities having several fields of different types.

| Size in Bytes | Round Trip CPU Time | |

|---|---|---|

| Message Pack | 242558 | 1303µs |

| Tree-Buf | 13545 | 608µs |

Tree-Buf compresses to less than 1/17 the size as compared to Message Pack, yet finishes reading and writing in less than 1/2 the time.

Entities look like this:

{

"createdAt": "1582140851",

"nft": {

"bids": [{

"bidder": "0x8a9d9b361dca26afecaf9d64f6b6e335e1b7df8a",

"blockNumber": "9521798",

"status": "open"

}],

"searchIsLand": false,

"searchIsWearableAccessory": false,

"wearable": {

"bodyShapes": ["BaseFemale"],

"category": "feet",

"collection": "halloween_2019",

"name": "Bee Suit Shoes",

"owner": { "mana": "0" },

"rarity": "epic",

"representationId": "bee_suit_feet"

}

},

"price": "200000000000000000000",

"status": "cancelled"

},This test compares the serialization of a GeoJson file containing a Feature Collection of MultiPolygon and Polygon Geometries for every country in the world.

| Size in Bytes | Round Trip CPU Time | |

|---|---|---|

| GeoJson | 24090863 | 407ms |

| Tree-Buf | 6865300 | 39ms |

| Tree-Buf 1m | 2268041 | 41ms |

In this test, Tree-Buf is over 10 times as fast as GeoJson, while producing a file that is 2/7th the size.

There is another entry for "Tree-Buf 1m". Here, compile-time options have been specified that allow Tree-Buf to use a lossy float compression technique. Code: tree_buf::experimental::encode_with_options(data, &encode_options! { options::LossyFloatTolerance(-12) }). 12 binary points of precision is better than 1-meter accuracy for latitude longitude points. This results in a file size that is just 1/10th the size of GeoJson, without sacrificing speed.

Another thing we can try is to selectively load some portion of the data using a modified schema. If we instruct Tree-Buf to only load the names and other attributes of the countries from the file without loading their geometries this takes 240µs - more than 1,500 times as fast as loading the data as GeoJson because Tree-Buf does not need to parse fields that do not need to be loaded, whereas Json needs to parse this data in order to skip over it.

BOSS (Baseball Open Source Software) is using Tree-Buf to store baseball statistics. These are early results from the WIP:

| Size | |

|---|---|

| CSV | 4577MiB |

| Tableau Hyper | 665MiB |

| Tree-Buf | 219MiB |

Tree-Buf is less than 1/20th the size of CSV in this case.

Tree-Buf is in early development, and the format is changing rapidly. It may not be a good idea to use Tree-Buf in production. If you do, make sure you test a lot and be prepared to do data migrations on every major release of the format. I take no responsibility for your poor choice of using Tree-Buf.

While the Tree-Buf format is language agnostic, it is currently only available for Rust.

Step 1: Add the latest version Tree-Buf to your cargo.toml

[dependencies]

tree-buf = "0.8.0"Step 2: Derive Encode and / or Decode on your structs.

use tree_buf::prelude::*;

#[derive(Encode, Decode, PartialEq)]

pub struct Data {

pub id: u32,

pub vertices: Vec<(f64, f64, f64)>,

pub extra: Option<String>,

}Step 3: Call encode and / or decode on your data.

pub fn round_trip() {

// Make some data

let data = Data {

id: 1,

vertices: vec! [

(10., 10., 10.),

(20., 20., 20.)

],

extra: String::from("Fast"),

};

// Encode to Vec<u8>

let bytes = encode(&data);

// Decode from &[u8]

let copy = decode(&bytes).unwrap();

// Success!

assert_eq!(©, &data);

}Done! You have mastered the use of Tree-Buf.

Tree-Buf makes it easy to see how your data is being compressed, and where you might optimize. For example, in the GraphQL benchmark we can run:

let sizes = tree_buf::experimental::stats::size_breakdown(&tb_bytes);

println!("{}", sizes.unwrap());and it will print:

Largest by path:

32000

data.orders.[1000].id.[32]

Object.Object.Array.Object.Array Fixed.U8 Fixed

5000

data.orders.[1000].createdAt

Object.Object.Array.Object.Prefix Varint

5000

data.orders.[1000].price

Object.Object.Array.Object.Prefix Varint

2836

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.representationId.values

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Dictionary.UTF-8

2452

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.name.values

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Dictionary.UTF-8

952

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.representationId.indices

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Dictionary.Simple16

948

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.name.indices

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Dictionary.Simple16

420

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.category.discriminants

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Enum.Simple16

356

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.collection.indices

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Dictionary.Simple16

288

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.rarity.discriminants

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Enum.Simple16

268

data.orders.[1000].status.discriminants

Object.Object.Array.Object.Enum.Simple16

236

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.bodyShapes.values.discriminants

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Array.Enum.Packed Boolean

120

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.bodyShapes.len.runs

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Array.RLE.Simple16

85

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.collection.values

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Dictionary.UTF-8

60

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.bodyShapes.len.values

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Array.RLE.Simple16

2

data.orders.[1000].nft.wearable.owner.mana.runs

Object.Object.Array.Object.Object.Object.Object.Bool RLE.Prefix Varint

Largest by type:

1x 32000 @ U8 Fixed

3x 10002 @ Prefix Varint

3x 5373 @ UTF-8

8x 3412 @ Simple16

1x 236 @ Packed Boolean

Other: 400

Total: 51423

Tree-Buf has canonical field names. That means you can say goodbye to #[serde(rename = "")] in Rust, [JsonProperty("")] in C#, and linter warnings in JavaScript. These are equivalent schemas in Tree-Buf:

// C#

class Klass {

public double FieldName;

}// TypeScript

class Klass {

fieldName: number

}// Rust

struct Klass {

field_name: f64

}How does Tree-Buf enable fast compression and serialization of real-world data?

- Organize the document into a tree/branches data model that clusters related data together.

- Use best-in-breed compression that is only available to typed vectors of primitive data.

- Amortize the cost of the self-describing schema.

To break these down concretely, it would be useful to track an example using real-world data. We'll take a look at the data, see how it maps to the Tree-Buf data model, and then see how Tree-Buf applies compression to each part of the resulting model.

Let's say that we want to store all of the game records for a round-robin tournament of Go. To follow along, you won't need any knowledge of the game. Suffice to say that it's played on a 19x19 grid, and players alternate placing white and black stones on the intersections of the board. It looks like this:

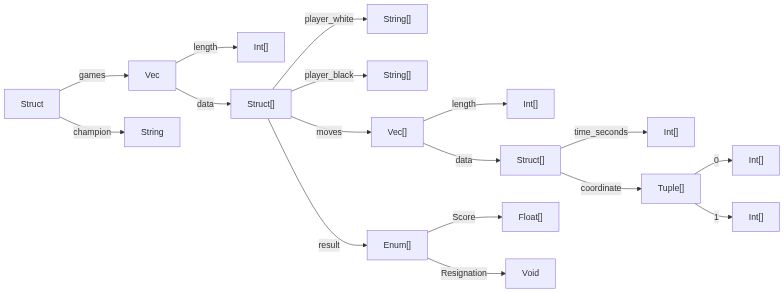

Here is what a simplified schema might look like for those recorded games.

struct Tournament {

games: Vec<Game>,

champion: String,

}

struct Game {

player_white: String,

player_black: String,

moves: Vec<Move>,

result: Result,

}

struct Move {

time_seconds: u32,

coordinate: (u8, u8),

}

enum Result {

Score(f32),

Resignation(String),

}And some sample data in that schema, given in JSON...

{

"champion": "Lee Changho",

"games": [

{

"white": "Honinbo Shusai",

"black": "Go Seigen",

"moves": [

{

"time_seconds": 4,

"coordinate": [16, 2],

},

{

"time_seconds": 9,

"coordinate": [2, 3],

},

"Followed by 246 more moves from the first game",

],

"result": 1.5,

},

"Followed by 119 more games from the tournament",

]

}Tree-Buf considers each path from the root through the schema as its own branch of a tree.

Here is an illustration of what that breakdown would look like for our schema:

Each branch stores all data accessible at that path through the schema, in the order it occurs in the document.

For example, there is an Int[] branch that exists at ->games->data->moves->data->time_seconds. This branch is an [] because it stores time samples for all moves for all games throughout the tournament. E.g.: [4, 9, ... 246 more time samples from the first game, ... time samples from the second game through the last game].

Similarly, the x-coordinate of all the moves from all the games through the path ->games->data->moves->data->coordinate->0 are stored contiguously: [16, 2, ... and so on]

Real-world data exhibits patterns. If your data does not exhibit some pattern, it's probably not very interesting.

The Tree-Buf data model clusters related data together so that it can take advantage of the patterns in your data using highly optimized compression libraries.

For example, values in the time_seconds field aren't random. They are monotonically increasing, and usually at a regular rate since games tend to proceed forward in a rhythm, with the occasional slowdown. The integer compression in Tree-Buf can take advantage of this. By utilizing, for example, delta encoding + Simple16, values can be represented usually in less than a single byte.

Coordinates in Go games aren't random either. A move in Go is very likely to be in the same quadrant of the board as the previous move, or even adjacent to the previous move. Again, utilizing, for example, delta encoding + Simple16 can get a series of adjacent moves down to about 2-3 bits per coordinate component within the same quadrant. It is crucial here that the Tree-Buf data model has split up the x and y coordinates into separate branches because these values cluster independently of each other. Interleaved x and y coordinates would appear more random to an integer compression library.

Even the names of the players aren't random. Because a round-robin tournament between 16 players requires 120 matches, the names of the players are highly redundant. Here too, we can keep track of which Strings have been written recently and refer to previous strings within a given list. In other formats the names of the players may appear far apart from each other in the final serialized document making it difficult for general purpose compression like gzip to find these patterns.

Add these to first-class support for enums, tuples, nullables, and a few other tricks, and it adds up to significant wins.

All of this compression in Tree-Buf happens behind the scenes, without any work on the part of the developer, or modification to the schema.

Let's compare these results to another popular binary format, Protobuf 3, to see the difference caused by this accumulation of many small wins. For now, let's only consider the moves vector since that's the largest portion of the data. Each move in Protobuf is a message. Each message in Protobuf is length delimited, requiring 1 byte. After the first 2 minutes and 7 seconds of the game clock, each time_seconds requires 2 bytes for the LEB128 encoded value and 1 byte for the field id - 3 bytes. For the coordinate field, we can cheat and implement this using a packed array. That doesn't exactly match the data model, but would require fewer bytes than an embedded message. A packed array requires 1 byte for the field id, 1 byte for the length prefix, and 1 byte each for the two values. Add these together, and you get 7 bytes per move, or 56 bits.

Depending on the game, Tree-Buf may require on average only 17 bits per move. ~4.5 bits each for the coordinate deltas, plus ~8 bits or less for time deltas of up to 2 minutes, 7 seconds. That is to say, the moves list requires about 3.3 times as much space in Protobuf 3 as compared to Tree-Buf (17 bits * 3.3 = 56 bits).

As compared to JSON? With 17 bits per move we can get... "t - Not quite "time_seconds":. The complete, minified move requires a whopping 336 bits, 19 times as much as Tree-Buf.

JetBrains has been kind enough to grant this project an open source license to use all their tools for free. I'm using CLion with the Rust plugin for Tree-Buf, but have also enjoyed using their other tools, like dotMemory, on other projects as well. Please check them out here: JetBrains.com