-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 37

130 The Widget Tree

Page Table of Contents

This section will give you a better understanding of how programming in Flutter [1] actually works. You will learn what Widgets [30] are, what types of Widgets Flutter has and lastly what exactly the Widget Tree is.

One sentence that is impossible to avoid when researching Flutter is:

“In Flutter, everything is a Widget.” [30]

But that is not really helpful, is it? Personally, I like Didier Boelens definition of Flutter Widgets better:

| 📙 | Widget | A visual component (or a component that interacts with the visual aspect of an application) [31] |

|---|

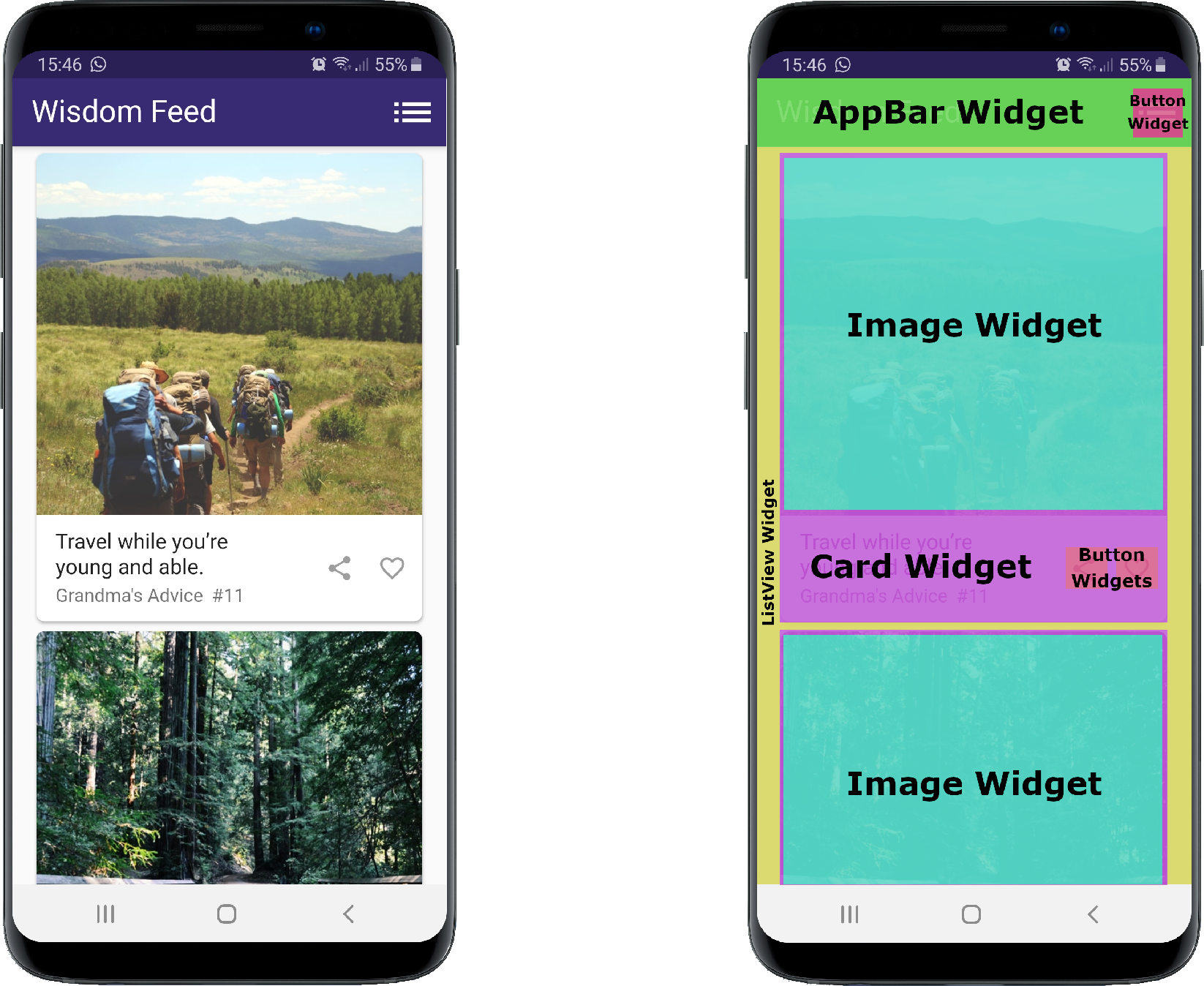

Let’s have look at an example, this is the Wisgen app [11], it displays an endless feed of wisdoms combined with vaguely thought-provoking stock images:

Figure 8: Wisgen Widgets [11]

All UI-Components of the app are Widgets. From high-level stuff like the AppBar and the ListView down to to the granular things like texts and buttons (I did not highlight every Widget on the screen to keep the figure from becoming overcrowded). In code, the build method of a card Widget would look something like this:

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Card(

shape: RoundedRectangleBorder( //Declare corners to be rounded

borderRadius: BorderRadius.circular(7),

),

elevation: 2, //Declare shadow drop

child: Column( //The child of the card are displayed in a column Widget

children: <Widget>[

_Image(_wisdom.imgUrl), //First child

_Content(_wisdom), //Second Child

],

),

);

}Code Snippet 5: Simplified Wisgen card Widget build method [11]

The _Image class generates a Widget that contains the stock image. The _Content class generates a Widget that displays the wisdom text and the buttons on the card. An important thing to note is that:

| ⚠ | Widgets in Flutter are always immutable [30] |

|---|

The build method of any given Widget can be called multiple times a second. And how often it is called exactly is never under your control, it is controlled by the Flutter Framework [32]. To make this rapid rebuilding of Widgets efficient, Flutter forces us developers to keep the build methods lightweight by making all Widgets immutable [33]. This means that all variables in a Widget have to be declared as final. They are initialized once and can not change over time. But your app never consists out of exclusively immutable parts, does it? Variables need to change, data needs to be fetched and stored. Almost any app needs some sort of mutable data. As mentioned in the previous chapter, in Flutter such data is called State [12]. No worries, how Flutter handles mutable State will be covered in the section Stateful Widgets down below, so just keep on reading.

When working with Flutter, you will inevitably stumble over the term Widget Tree, but what is a Widget Tree? A UI in Flutter is nothing more than a tree of nested Widgets. Let’s have a look at the Widget Tree of our example from figure 8. Note the card Widgets on the right-hand side of the diagram. There you can see how the code from snippet 5 translates to Widgets in the Widget Tree.

Figure 9: Wisgen Widget Tree [11]

If you have previously built an app with Flutter, you have definitely encountered BuildContext [34]. It is passed in as a variable in every Widget build method in Flutter.

| 📙 | BuildContext | A reference to the location of a Widget within the tree structure of all the Widgets that have been built [31] |

|---|

The BuildContext contains information about each ancestor leading down to the Widget that the BuildContext belongs to. It is an easy way for a Widget to access all its ancestors in the Widget Tree. Accessing a Widgets descendants through the BuildContext is possible, but not advised and inefficient. So in short: It s very easy for a Widget at the bottom of the tree to get information from Widgets at the top of the tree but not vice-versa [31]. For example, the image Widget from figure 9 could access its ancestor card Widget like this:

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//going up the Widget Tree:

//(Image [me]) -> (Column) -> (Card) [!] first match, so this one is returned

Card ancestorCard = Card.of(context);

return CachedNetworkImage(

...

);

}Code Snippet 6: Hypothetical Wisgen image Widget [11]

Alright, but what does that mean for me as a Flutter developer? It is important to understand how data in Flutter flows through the Widget Tree: Downwards. You want to place information that is required by multiple Widgets above them in the tree, so they can both easily access it through their BuildContext. Keep this in mind, for now, I will explain this in more detail in the chapter Architecting a Flutter App.

There are three types of Widgets in the Flutter Framework. I will now showcase their differences, their lifecycles, and their respective use-cases.

This is the most basic of the three and likely the one you’ll use the most when developing an app with Flutter. Stateless Widgets [32] are initialized once with a set of parameters and those parameters will never change from there on out. Let’s have a look at an example. This is a simplified version of the card Widget from figure 8:

class WisdomCard extends StatelessWidget {

static const double _cardElevation = 2;

static const double _cardBorderRadius = 7;

final Wisdom _wisdom;

WisdomCard(this._wisdom);

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {...}

...

}Code Snippet 7: Simplified Wisgen card Widget class [11]

As you can see, it has some constant values for styling, a wisdom object that is passed into the constructor and a build method. The wisdom object contains the wisdom text and the hyperlink to the stock image.

One thing I want to point out here is that even if all fields are final in a StatelessWidget, it can still change to a degree. A ListView Widget is also a Stateless for example. It has a final reference to a list. Things can be added or removed from that list without the reference in the ListView Widget changing. So the ListView remains immutable and Stateless while the things it displays can change [35].

The Lifecycle of Stateless Widgets is very straight forward [31]:

class MyWidget extends StatelessWidget {

///Called first

///

///Use for initialization if needed

MyClass({ Key key }) : super(key: key);

///Called multiple times a second

///

///Keep lightweight (!)

///This is where the actual UI is build

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

...

}

}Code Snippet 8: Stateless Widget Lifecycle

I explained what State is in the Chapter Thinking Declaratively. But just as a reminder:

| 📙 | State | Any data that can change over time [12] |

|---|

A Stateful Widget [13] always consists of two parts: An immutable Widget and a mutable State. The immutable Widget’s responsibility is to hold onto that State, the State itself has the mutable data and builds the actual UI element [36]. Let’s have a look at an example. This is a simplified version of the WisdomFeed from Figure 8. The WisdomBloc is responsible for generating and caching wisdoms that are then displayed in the Feed. More on that in the chapter Architecting a Flutter App.

///Immutable Widget

class WisdomFeed extends StatefulWidget {

@override

State<StatefulWidget> createState() => WisdomFeedState();

}

///Mutable State

class WisdomFeedState extends State<WisdomFeed>{

WisdomBloc _wisdomBloc; //Mutable / Not final (!)

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

//This is where the actual UI element/Widget is build

...

}

}Code Snippet 9: Simplified Wisgen WisdomFeed [11]

If you are anything like me, you will ask yourself: “why is this split into 2 parts? The StatefulWidget is not really doing anything.” Well, The Flutter Team wants to keep Widgets always immutable. The only way to keep this statement universally true is to have the StatefulWidget hold onto the State but not actually be the State [36], [37].

State objects have a long lifespan in Flutter. They will stick around during rebuilds or even if the Widget that they are linked to gets replaced [36]. So in this example, no matter how often the WisdomFeed gets rebuild and no matter if the user switches pages, the cached list of wisdoms (WisdomBloc) will stay the same until the app is shut down.

The Lifecycle of State Objects/StatefulWidgets is a little bit more complex. I will only showcase a boiled-down version here. It contains all the methods you’ll need for this guide. You can read the full Lifecycle here: Lifecycle of StatefulWidgets [37].

class MyWidget extends StatefulWidget {

///Called immediately when first building the StatefulWidget

@override

State<StatefulWidget> createState() => MySate();

}

class MyState extends State<MyWidget>{

///Called after constructor

///

///Called exactly once

///Use this to subscribe to Streams or for any initialization

@override

initState(){...}

///Called multiple times a second

///

///Keep lightweight (!)

///This is where the actual UI element/Widget is build

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context){...}

///Called once before the State is disposed (app shut down)

///

///Use this for your clean up and to unsubscribe from Streams

@override

dispose(){...}

}Code Snippet 10: State Objects/StatefulWidgets Lifecycle

Keep in mind, to improve performance, you always want to rely on as few Stateful Widgets as possible. There are essentially two reasons to choose a Stateful Widget over a Stateless one:

- The Widget needs to hold any kind of data that has to change during its lifetime.

- The Widget needs to dispose of anything or clean up after itself at the end of its lifetime.

I will not go in detail on Inherited Widgets [38] here. When using the BLoC library [39], which I will teach you in the chapter Architecting a Flutter-App, you will most likely never create an Inherited Widgets yourself. But in short: They are a way to expose data from the top of the Widget Tree to all their descendants. And they are used as the underlying technology of the BLoC library.

This Guide is licensed under the Creative Commons License (Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International)

Author: Sebastian Faust.