This repository has been archived by the owner on Mar 13, 2024. It is now read-only.

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 2

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

- Loading branch information

Showing

1 changed file

with

83 additions

and

1 deletion.

There are no files selected for viewing

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -1 +1,83 @@ | ||

| # PageRank Project | ||

|

|

||

| # 🔖 PageRank Project | ||

|

|

||

| **Objective:** Write an AI to rank web pages by importance. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 📺 Demonstration | ||

|

|

||

| ``` | ||

| $ python pagerank.py corpus0 | ||

| PageRank Results from Sampling (n = 10000) | ||

| 1.html: 0.2223 | ||

| 2.html: 0.4303 | ||

| 3.html: 0.2145 | ||

| 4.html: 0.1329 | ||

| PageRank Results from Iteration | ||

| 1.html: 0.2202 | ||

| 2.html: 0.4289 | ||

| 3.html: 0.2202 | ||

| 4.html: 0.1307 | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| ## 🌉 Background | ||

|

|

||

| When search engines like Google display search results, they do so by placing more “important” and higher-quality pages higher in the search results than less important pages. But how does the search engine know which pages are more important than other pages? | ||

|

|

||

| One heuristic might be that an “important” page is one that many other pages link to, since it’s reasonable to imagine that more sites will link to a higher-quality webpage than a lower-quality webpage. We could therefore imagine a system where each page is given a rank according to the number of incoming links it has from other pages, and higher ranks would signal higher importance. | ||

|

|

||

| But this definition isn’t perfect: if someone wants to make their page seem more important, then under this system, they could simply create many other pages that link to their desired page to artificially inflate its rank. | ||

|

|

||

| For that reason, the PageRank algorithm was created by Google’s co-founders (including Larry Page, for whom the algorithm was named). In PageRank’s algorithm, a website is more important if it is linked to by other important websites, and links from less important websites have their links weighted less. This definition seems a bit circular, but it turns out that there are multiple strategies for calculating these rankings. | ||

|

|

||

| ### Random Surfer Model | ||

|

|

||

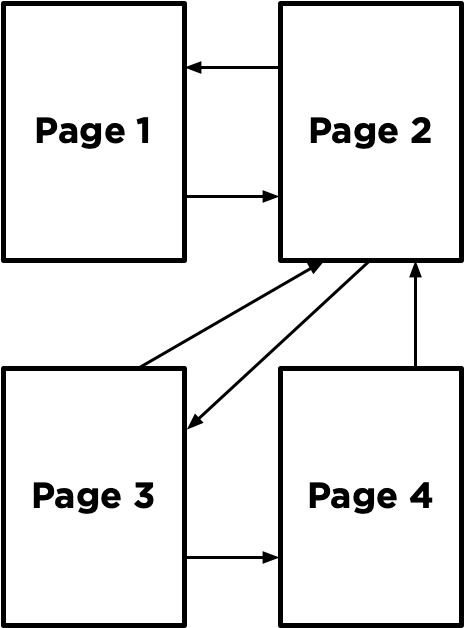

| One way to think about PageRank is with the random surfer model, which considers the behavior of a hypothetical surfer on the internet who clicks on links at random. Consider the corpus of web pages below, where an arrow between two pages indicates a link from one page to another. | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| The random surfer model imagines a surfer who starts with a web page at random, and then randomly chooses links to follow. If the surfer is on Page 2, for example, they would randomly choose between Page 1 and Page 3 to visit next (duplicate links on the same page are treated as a single link, and links from a page to itself are ignored as well). If they chose Page 3, the surfer would then randomly choose between Page 2 and Page 4 to visit next. | ||

|

|

||

| A page’s PageRank, then, can be described as the probability that a random surfer is on that page at any given time. After all, if there are more links to a particular page, then it’s more likely that a random surfer will end up on that page. Moreover, a link from a more important site is more likely to be clicked on than a link from a less important site that fewer pages link to, so this model handles weighting links by their importance as well. | ||

|

|

||

| One way to interpret this model is as a Markov Chain, where each page represents a state, and each page has a transition model that chooses among its links at random. At each time step, the state switches to one of the pages linked to by the current state. | ||

|

|

||

| By sampling states randomly from the Markov Chain, we can get an estimate for each page’s PageRank. We can start by choosing a page at random, then keep following links at random, keeping track of how many times we’ve visited each page. After we’ve gathered all of our samples (based on a number we choose in advance), the proportion of the time we were on each page might be an estimate for that page’s rank. | ||

|

|

||

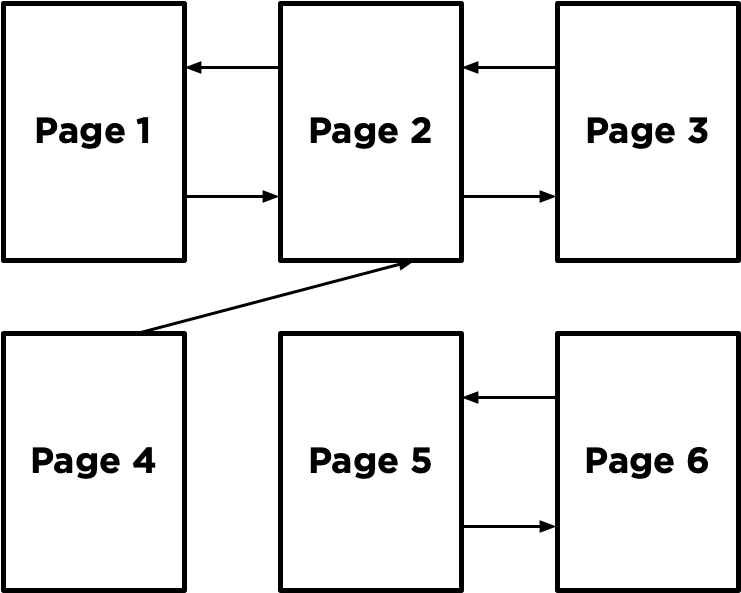

| However, this definition of PageRank proves slightly problematic, if we consider a network of pages like the below. | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| Imagine we randomly started by sampling Page 5. We’d then have no choice but to go to Page 6, and then no choice but to go to Page 5 after that, and then Page 6 again, and so forth. We’d end up with an estimate of 0.5 for the PageRank for Pages 5 and 6, and an estimate of 0 for the PageRank of all the remaining pages, since we spent all our time on Pages 5 and 6 and never visited any of the other pages. | ||

|

|

||

| To ensure we can always get to somewhere else in the corpus of web pages, we’ll introduce to our model a damping factor `d`. With probability `d` (where `d` is usually set around `0.85`), the random surfer will choose from one of the links on the current page at random. But otherwise (with probability `1 - d`), the random surfer chooses one out of all of the pages in the corpus at random (including the one they are currently on). | ||

|

|

||

| Our random surfer now starts by choosing a page at random, and then, for each additional sample we’d like to generate, chooses a link from the current page at random with probability `d`, and chooses any page at random with probability `1 - d`. If we keep track of how many times each page has shown up as a sample, we can treat the proportion of states that were on a given page as its PageRank. | ||

|

|

||

| ### Iterative Algorithm | ||

|

|

||

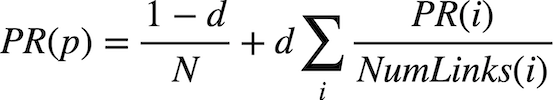

| We can also define a page’s PageRank using a recursive mathematical expression. Let `PR(p)` be the PageRank of a given page `p`: the probability that a random surfer ends up on that page. How do we define `PR(p)`? Well, we know there are two ways that a random surfer could end up on the page: | ||

|

|

||

| 1. With probability `1 - d`, the surfer chose a page at random and ended up on page `p`. | ||

| 2. With probability `d`, the surfer followed a link from a page `i` to page `p`. | ||

|

|

||

| The first condition is fairly straightforward to express mathematically: it’s `1 - d` divided by `N`, where `N` is the total number of pages across the entire corpus. This is because the `1 - d` probability of choosing a page at random is split evenly among all `N` possible pages. | ||

|

|

||

| For the second condition, we need to consider each possible page `i` that links to page `p`. For each of those incoming pages, let `NumLinks(i)` be the number of links on page `i`. Each page `i` that links to `p` has its own PageRank, `PR(i)`, representing the probability that we are on page `i` at any given time. And since from page `i` we travel to any of that page’s links with equal probability, we divide `PR(i)` by the number of links `NumLinks(i)` to get the probability that we were on page `i` and chose the link to page `p`. | ||

|

|

||

| This gives us the following definition for the PageRank for a page `p`. | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| In this formula, `d` is the damping factor, `N` is the total number of pages in the corpus, `i` ranges over all pages that link to page `p`, and `NumLinks(i)` is the number of links present on page `i`. | ||

|

|

||

| How would we go about calculating PageRank values for each page, then? We can do so via iteration: start by assuming the PageRank of every page is `1 / N` (i.e., equally likely to be on any page). Then, use the above formula to calculate new PageRank values for each page, based on the previous PageRank values. If we keep repeating this process, calculating a new set of PageRank values for each page based on the previous set of PageRank values, eventually the PageRank values will converge (i.e., not change by more than a small threshold with each iteration). | ||

|

|

||

| ## 🧐 Understanding | ||

|

|

||

| Open up `pagerank.py`. Notice first the definition of two constants at the top of the file: `DAMPING` represents the damping factor and is initially set to `0.85`. `SAMPLES` represents the number of samples we’ll use to estimate PageRank using the sampling method, initially set to 10,000 samples. | ||

|

|

||

| Now, take a look at the `main` function. It expects a command-line argument, which will be the name of a directory of a corpus of web pages we’d like to compute PageRanks for. The `crawl` function takes that directory, parses all of the HTML files in the directory, and returns a dictionary representing the corpus. The keys in that dictionary represent pages (e.g., `"2.html"`), and the values of the dictionary are a set of all of the pages linked to by the key (e.g. `{"1.html", "3.html"}`). | ||

|

|

||

| The `main` function then calls the `sample_pagerank` function, whose purpose is to estimate the PageRank of each page by sampling. The function takes as arguments the corpus of pages generated by `crawl`, as well as the damping factor and number of samples to use. Ultimately, `sample_pagerank` should return a dictionary where the keys are each page name and the values are each page’s estimated PageRank (a number between 0 and 1). | ||

|

|

||

| The `main` function also calls the `iterate_pagerank` function, which will also calculate PageRank for each page, but using the iterative formula method instead of by sampling. The return value is expected to be in the same format, and we would hope that the output of these two functions should be similar when given the same corpus! |