Deep Dive In :

Docker is here and there’s no point hiding. In fact, if you want the best jobs working on the best tehnologies, you need to know Docker and containers.

If you think Docker is just for developers, prepare to have your world turned upside-down. Most applications, even the funky cloud-native microservices ones, need high-performance production-grade infrastructure to run on. If you think traditional developers are going to take care of that, think again. To cut a long story short, if you want to thrive in the modern cloud-first world, you need to know Docker. But don’t stress, this book will give you all the skills you need.

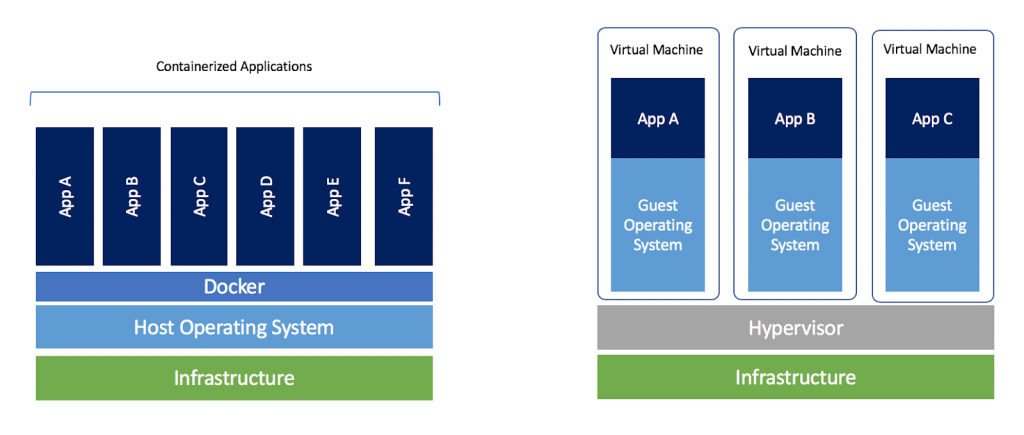

Containers have revolutionized the way applications are deployed and managed. Traditionally, each application required its own server, leading to inefficiencies and wastage. VMware's virtual machines (VMs) offered a solution by allowing multiple applications to run on a single server, optimizing resource utilization. However, VMs have drawbacks, such as resource-intensive operating systems and slow boot times.

Enter containers. Popularized by tech giants like Google, containers offer a lightweight alternative to VMs. Unlike VMs, containers share the host's operating system, leading to significant resource savings and improved portability. They boot quickly and are easily portable across different environments, from laptops to cloud platforms. Containers represent a more efficient and agile approach to application deployment, reducing costs and simplifying maintenance.

Linux containers, a cornerstone of modern computing, owe their existence to extensive collaboration and contributions within the Linux community, notably from Google LLC. Key technologies like kernel namespaces, control groups, union filesystems, and Docker have fueled the exponential growth of containers.

Despite their complexity, containers were made accessible to a broader audience with the advent of Docker. While other operating system virtualization technologies predate Docker, such as BSD Jails and Solaris Zones, this book focuses on modern containers popularized by Docker.

Docker, Inc. simplified container usage, democratizing their adoption and making them accessible to all. We'll delve deeper into Docker's role in the next chapter.

Docker is software for creating, managing, and orchestrating containers on Linux and Windows. It's built from various tools within the Moby open-source project. Docker, Inc., the company behind it, was founded by Solomon Hykes but he's no longer with the company. Their focus is on simplifying the process of running code from your laptop in the cloud.

When most people talk about Docker, they’re referring to the technology that runs containers. However, there are at least three things to be aware of when referring to Docker as a technology:

- The runtime

- The daemon (a.k.a. engine)

- The orchestrator

this figure shows the three layers and will be a useful reference as we explain each component.

Docker's runtime architecture involves two main components: runc and containerd. Runc, the low-level runtime, handles starting and stopping containers by interacting with the OS. Containerd, the higher-level runtime, manages the entire container lifecycle, including image pulling and network management. Dockerd, the Docker daemon, sits above containerd and provides an easy-to-use interface for managing containers, images, volumes, and networks. Additionally, Docker supports cluster management through Docker Swarm, although Kubernetes is becoming the preferred choice for most users.

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) is a governing body responsible for standardizing fundamental components of container infrastructure, focusing on image format and container runtime. Initially, CoreOS introduced an open standard called appc and an implementation called rkt, which competed with Docker. To avoid fragmentation, the industry came together to form the OCI, resulting in the publication of two specifications: the image-spec and the runtime-spec. These specifications, akin to standardized rail tracks, allow for innovation while ensuring compatibility across container platforms. The OCI's standards have greatly influenced Docker's architecture, aligning it with OCI runtime spec starting from Docker 1.11.

The Docker engine, often simply referred to as Docker, is the core software responsible for running and managing containers. Think of it akin to VMware's ESXi. It's modular in design, built from various specialized tools adhering to open standards like those set by the Open Container Initiative (OCI). Similar to a car engine composed of specialized parts, the Docker Engine comprises components like the Docker daemon, containerd, runc, and plugins for networking and storage. Together, these components create and run containers.

When Docker was first released, it comprised two main components: the Docker daemon and LXC. The daemon, a monolithic binary, encompassed the Docker client, API, container runtime, and more. LXC provided access to essential container features in the Linux kernel, like namespaces and control groups. However, the reliance on LXC posed challenges as it was Linux-specific and hindered multi-platform aspirations. Docker, Inc. addressed this by developing libcontainer, a platform-agnostic tool to replace LXC. Libcontainer became the default execution driver in Docker 0.9. Additionally, Docker, Inc. recognized the limitations of the monolithic daemon and embarked on a significant effort to modularize it. This involved breaking down the daemon into smaller, specialized tools, aligning with the Unix philosophy of building modular components. As a result, all container execution and runtime code were extracted from the daemon and refactored into separate, interchangeable tools.

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) defined two container-related standards: the Image spec and the Container runtime spec, both released as version 1.0 in July 2017. Stability is paramount, with minimal changes expected. The latest Image spec is v1.0.1 (November 2017), and the latest runtime spec is v1.0.2 (March 2020).

Docker, Inc. played a significant role in developing these standards, contributing extensively. Since Docker 1.11 (early 2016), the Docker engine closely adheres to OCI specifications. Container runtime code is separated from the Docker daemon, implemented in an OCI-compliant layer. Docker defaults to using runc, the reference implementation of the OCI container-runtime-spec.

Additionally, the containerd component ensures Docker images are compliant OCI bundles.

Runc is the primary implementation of the OCI container-runtime-spec, developed with significant input from Docker, Inc. It serves as a lightweight CLI wrapper for libcontainer, which replaced LXC in Docker's early architecture. Runc's main function is to create containers efficiently and quickly. As a standalone tool, it lacks the rich features of the Docker engine but provides bare-bones, low-level container management. This simplicity allows for easy downloading and building of the binary for experimentation with OCI containers. The layer where runc operates is often referred to as "the OCI layer".

Docker stripped container execution logic from its daemon, creating containerd (pronounced container-dee) to manage container lifecycle operations such as start, stop, pause, and remove. Originally designed to be lightweight and focused solely on lifecycle operations, containerd now encompasses additional functionalities like image pulls, volumes, and networks.

While containerd's functionality expanded to accommodate projects like Kubernetes, its modular design allows users to select specific features. Developed by Docker, Inc., containerd was donated to the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) and has since graduated as a fully stable CNCF project, suitable for production use. You can find the latest releases [here](link to releases).

In this chapter, we'll dive deep into Docker images. The aim is to give you a solid understanding of what Docker images are, how to perform basic operations, and how they work under-the-hood. We'll split this chapter into the following sections:

A Docker image is a self-contained package containing everything needed for an application to run, including code, dependencies, and OS constructs. It's akin to a VM template for former VM admins or a class for developers.

You obtain Docker images by pulling them from an image registry, with Docker Hub being the most common. Pulling downloads the image to your local Docker host for container instantiation.

Images consist of stacked layers, forming a single object. They contain a streamlined OS and necessary files/dependencies. Typically small in size for fast and lightweight containerization (though Microsoft images can be large).

Understanding Docker images gives you a foundational grasp of containerization. Ready for the mind-blowing part? Let's go! 😎

We've mentioned a couple of times already that images are like stopped containers (or classes if you're a developer). In fact, you can stop a container and create a new image from it. With this in mind, images are considered build-time constructs, whereas containers are run-time constructs.

-

Relationship between Images and Containers: Images are used to create containers, and once a container is started from an image, they become dependent on each other. Images cannot be deleted until the last container using it has been stopped and destroyed.

-

Size of Images: Docker images are designed to be small, containing only the necessary code and dependencies for running a specific application or service. This results in stripped-down images without non-essential components like shells or kernels.

-

Pulling Images: Docker images are fetched from centralized repositories called image registries, such as Docker Hub. Images are pulled onto a Docker host using the

docker image pullcommand. Images can be tagged with different versions, and Windows-based images tend to be larger than Linux-based ones. -

Image Naming: Images are stored in image registries, and Docker Hub is the most common one. Official repositories contain curated images, while unofficial ones may have less reliable content. Images are named using the format

<repository>:<tag>. -

Images and Layers: Docker images are composed of layers, each representing a set of changes to the filesystem. Layers are stacked on top of each other to create the final image. The

docker historyanddocker inspectcommands can be used to inspect image layers. -

Sharing Image Layers: Multiple images can share the same layers, leading to space and performance efficiencies. Docker automatically recognizes and reuses layers when pulling similar images.

-

Pulling Images by Digest: Docker images can also be pulled using their digest, which is a unique identifier for the image content. This ensures consistency and prevents accidental use of incorrect image versions.

List all local Docker images :

docker image ls

List all local Docker images with additional details :

docker image ls -a

List all local Docker images with a specific name :

docker image ls <image_name>

List all local Docker images with a specific tag :

docker image ls <image_name>:<tag>

List all local Docker images with a specific repository :

docker image ls <repository>/*

List all local Docker images with a specific repository and tag :

docker image ls <repository>/*:<tag>

Pull a Docker image from a registry :

docker image pull <image_name>

Remove a local Docker image :

docker image rm <image_name>

Remove all local Docker images :

docker image rm $(docker image ls -a -q)

Tag a Docker image with a different name :

docker image tag <source_image> <target_image>

Push a Docker image to a registry :

docker image push <image_name>

Inspect details of a Docker image :

docker image inspect <image_name>

Show the history of a Docker image :

docker image history <image_name>

A container is a lightweight and isolated environment that allows you to run applications consistently across different computing environments. It encapsulates the application and its dependencies, making it portable and easy to deploy.

Containers are created from container images, which contain everything needed for an application to run, including the code, dependencies, and operating system constructs. Docker is a popular tool for managing containers and provides a platform for building, distributing, and running containerized applications.

Containerization offers benefits such as improved scalability, resource efficiency, and isolation. It enables developers to package applications with their dependencies, ensuring consistent behavior across different environments.

To use Docker on macOS, you can install Docker Desktop, which runs within a lightweight Linux VM. For 42 students, there is a script available in the 42toolbox repository that allows you to use Docker in goinfre.

Get started with containers and unlock the power of application deployment and management! 🚀

A container is a standard unit of software that packages up code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another. A Docker container image is a lightweight, standalone, executable package that includes everything needed to run a piece of software, including the code, a runtime, libraries, environment variables, and config files.

Containers are an abstraction at the app layer that packages code and dependencies together. Multiple containers can run on the same machine and share the OS kernel with other containers, each running as isolated processes in user space. Containers take up less space than VMs (container images are typically tens of MBs in size), can handle more applications and require fewer VMs and Operating systems.

- Agile application creation and deployment: Increased ease and efficiency of container image creation compared to VM image use.

- Continuous development, integration, and deployment: Provides for reliable and frequent container image build and deployment with quick and easy rollbacks (due to image immutability).

- Dev and Ops separation of concerns: Create application container images at build/release time rather than deployment time, thereby decoupling applications from infrastructure.

- Observability: Not only surfaces OS-level information and metrics, but also application health and other signals.

- Environmental consistency across development, testing, and production: Runs the same on a laptop as it does in the cloud.

- Cloud and OS distribution portability: Runs on Ubuntu, RHEL, CoreOS, on-prem, Google Kubernetes Engine, and anywhere else.

- Application-centric management: Raises the level of abstraction from running an OS on virtual hardware to running an application on an OS using logical resources.

- Loosely coupled, distributed, elastic, liberated micro-services: Applications are broken into smaller, independent pieces and can be deployed and managed dynamically – not a monolithic stack running on one big single-purpose machine.

- Resource isolation: Predictable application performance.

- Resource utilization: High efficiency and density.

Containers and virtual machines have similar resource isolation and allocation benefits, but function differently because containers virtualize the operating system instead of hardware. Containers are more portable and efficient.

Docker volumes are the preferred mechanism for persisting data generated by and used by Docker containers. While bind mounts are dependent on the directory structure and OS of the host machine, volumes are completely managed by Docker. Volumes have several advantages over bind mounts:

- Volumes are easier to back up or migrate than bind mounts.

- You can manage volumes using Docker CLI commands or the Docker API.

- Volumes work on both Linux and Windows containers.

- Volumes can be more safely shared among multiple containers.

- Volume drivers allow you to store volumes on remote hosts or cloud providers, to encrypt the contents of volumes, or to improve performance with caching.

You can create a volume explicitly using the docker volume create command, or Docker can create a volume during container or service creation.

When you create a volume, it is stored within a directory on the Docker host. When you mount the volume into a container, this directory is what is mounted into the container. This is similar to the way that bind mounts work, except that volumes are managed by Docker and are isolated from the core functionality of the host machine.

A new volume’s contents can be pre-populated by a container. For instance, you can create a volume with a container, and then mount it in another container. In the example below, an nginx container creates the volume myvol2, and the alpine container mounts the volume and writes a message to a file:

$ docker run -d --name=nginxtest -v myvol2:/app nginx:latest

$ docker run --rm --volumes-from nginxtest alpine cat /app/messageYou can remove unused volumes using docker volume prune.

When you mount a volume, it may be named or anonymous. Anonymous volumes are not given an explicit name when they are first mounted into a container, so Docker gives them a random name that is guaranteed to be unique within a given Docker host. Besides the name, named and anonymous volumes behave in the same ways.

Docker networking allows you to define your own network space and manage how your Docker containers communicate with each other and with the outside world. Docker provides different networking drivers to suit different needs. The most commonly used drivers are bridge, host, and overlay.

- The default network driver. If you don’t specify a driver, this is the type of network you are creating. Bridge networks are usually used when your applications run in standalone containers that need to communicate.

- Host networks are best when the network stack should not be isolated from the Docker host, but you want other aspects of the container to be isolated.

- Overlay networks connect multiple Docker daemons together and enable swarm services to communicate with each other. You can also use overlay networks to facilitate communication between a swarm service and a standalone container, or between two standalone containers on different Docker daemons.

You can create a network using the docker network create command, and Docker can create a network automatically during swarm or service creation.

You can inspect a network using docker network inspect my_bridge_network.

You can remove unused networks using docker network prune

When you create a service and do not specify a network, the service is automatically attached to the default ingress network.

MacOs Docker: Desktop for Mac provides a convenient way to run Docker and Kubernetes on your macOS system. However, it operates within a lightweight Linux VM rather than natively on the macOS kernel. This means Docker commands run as expected, but only Linux-based Docker containers are supported. Installation is straightforward; simply search for "install Docker Desktop," download the installer, and follow the instructions. You can choose between stable and edge channels for feature updates. After installation, start Docker Desktop from the Launchpad, and use the Docker commands in the terminal as usual. Remember, while the Docker client is native to macOS, the Docker daemon runs within the Linux VM.

For 42 Student you can run the script ./init_docker.sh inside this repo https://github.com/alexandregv/42toolbox.git to use docker in goinfre !